Thursday, October 28, 2010

March 2011: Johnny Cash's American Recordings

You can listen to Tony Tost's America here and I hope you enjoy this (unedited) extract from the book, which should be available in late March:

***

“My song ain’t done playing yet,” Cash sang in 1976, “so I believe I’ll hit the road and go.” On his staggeringly odd, nearly unlistenable concept album called The Rambler, Cash tried to update his conceptual records about cowboys, Indians and trains to a more contemporary image repertoire, transforming himself into an interstate rambler, a sort of mid-70s Dixie Kerouac.

Cash was as near to ordinary as he would ever be in the mid to late 1970s — he wouldn’t sink to sub-ordinary until the next decade — and in his quest to again be found relevant he alternated between updating and retrograding himself. After the attempted self-reinvention of The Rambler flopped, Cash beckoned the obsessions of his earlier self by recording The Last Gunfighter Ballad, featuring Guy Clark’s fine title track, which concerned a lonesome survivor of the West, a song that caustically bid the gunfighter and his landscape farewell. In his liner notes to the album, Cash recalled his habit in the 1950s and 1960s of practicing his fast draw, “shootin’ every tree in the yard full of holes” and staging gunfight duels, using blanks, with some of his buddies at that time. “I had a showdown with Johnny Western one night in Minneapolis,” Cash wrote, “and he killed me seven times in a row.” In a hotel hallway in Australia, Cash and Sammy Davis Jr. dueled, with the one-eyed hipster proving triumphant. “It only takes one good eye to shoot, Cash,” said Davis Jr.

On the album’s title track, Cash narrated the story of a displaced elder who tells stories of the old West no one believes anymore since “the streets are empty and the blood’s all dried.” Having spent his post-Folsom glow recasting himself as the patriotic, holy and happy husband of June Carter, Cash could have been reading Clark’s lyrics as a portraiture of himself, a once vigorous, dangerous man whom history had now passed by. In Clark’s song, the last gunfighter recalls how he used to stand in the street outside the saloon, back before the street was even paved, shooting down the slothful and foolish. “The last of a breed,” the song declares. As the song continues, the old man begins hearing vengeful ghosts out on the pavement; he heads out in the hot sun, reliving his past “and he’s killed by a car as he goes for his gun.”

Comically pathetic, the song illustrates just how the crowded confines of contemporary life offer little elbow room for old time American machismo, how the road limits freedoms as much as it offers them up. On Springsteen’s Nebraska, the car and the road likewise play a cruel game of trap and release. Even if bad brother Frankie is able to flee the repercussions of his violence in “Highway Patrolman,” each family member of “Used Cars” must silently confront their shared residence in the lower realm of the social hierarchy when driving around their neighborhood in a pre-owned vehicle. The narrator of “State Trooper” is simply a beast, caged inside his automobile with nothing to listen to but the radio’s static; the only remnants of the wide open American ideal of freedom still available to him are not freedoms at all but mere gestures: his defiant shout of “high-ho silver-o, deliver me from nowhere” at the close of the song, and the final battle cries he lets out as the song pulses into silence.

Cash was at his best when he focused on men caught between eras, men whose interiors matched the landscapes of some different, often imaginary time. The most compelling song on The Last Gunfighter Ballad was a Cash original, staging one possible consequence of such entrapment. In Cash’s reimagining of the ancient Barbara Allen legend, a song called “The Ballad of Barbara” (originally the b-side to Cash’s 1973 single, “Praise the Lord and Pass the Soup,” which is just as awful as you imagine), the narrator recalls his childhood in a southern town, where he worked the fields and traveled through the woods, in tune with the land and seasons and the smells of creation. He is eventually drawn away by the promises of a cultured city life, however, with its “breathtaking lofty steeples,” and he enters a world of steel and concrete that separates him from those vital sources. In that city, Cash’s narrator finds a girl and marries her and, without much surprise, soon longs to go back to his land and people, to return to the landscape that created him and that still is within him. At the moment of the narrator’s leaving, however, Cash’s investment in the folk tradition reveals itself with an image worthy of Ovid himself. “Then her hazel eyes turned away from me, with a look that wasn’t very pretty,” Cash sings. “And she turned into concrete and steel, and she said ‘I’ll take the city.’”

After his darling transforms into the unnatural elements that created her, Cash’s narrator hits the interstate that first brought him to the city (though Cash and co-producer Charlie Bragg, in an odd bit of inspiration, decided to soundtrack his rambles with percussive hoofbeats), hitchhiking his way back to the country life he had left behind. True to his cyclical method, Cash recorded the song yet again on the underrated, underheard Johnny Cash is Coming to Town, released in 1987. The album featured a superior version of “The Ballad of Barbara” along with its strong covers of Elvis Costello, Guy Clark, Merle Travis and James Talley, among others. But even on this album, one that contains such a disavowal of progress as “The Ballad of Barbara,” Cash again sounded like an old man trying to keep up with the times and with Jack Clement’s manic, machinic production.

The initial shock of American Recordings upon its release was that Cash had suddenly turned his back on the waves of progress and innovation he had spent decades chasing. Instead, he transmuted himself into progress’s shadow, haunting it. No longer attaching himself to automobiles and starships — though he would record a wrenchingly lovely version of Springsteen’s “Further On Up the Road” towards the very end of his American ride — Cash instead took a giant leap back, returning to the terrain that forged him. Suddenly, he was as incongruous as the gunfighter and the locomotive, a true folk image: an American world of Ovidian possibilities of tragedy and transformation seemed to come alive with a gesture of his hand, waving away the backing band and the innovative production values. Instead of chasing ghosts on the pavement he was creating a world in which only ghosts could thrive. It produced a singular effect, an aural profile of a man who was absolutely alone within our era but who contained many eras within himself.

It was Cash expressing not only the weight of solitude but also the transformational powers of a layered solitude. He had first forged the idea for such a stripped-down record way back in the 1960s, in a conversation with Marty Robbins, after noting Robbins’ tendency to end his concerts with intimate, acoustic numbers, inviting the audience to his own private campfire. Cash had always wanted to call his own imagined acoustic album Late and Alone With Johnny Cash, a title that conveys a particularly threatening edge to its intimacy. And by 1994, after so many dry, desperate years, late and alone was likely the only place where Cash could become a killer and a prophet once again. Late and Alone: this was the very flag beneath which Timothy McVeigh and Harriet Tubman, Col. Tom Parker and John Brown, Thirteen and Andrew Jackson had contrived the plans that tied their names to a bigger fate. Late and Alone: a midnight of the mind, the very logic of reckoning.

***

Wednesday, October 27, 2010

Junk Mail?

Home Recording Contest Results Are In!

Tuesday, October 26, 2010

The League Table, October 2010

In that context, the Brian Eno book is doing remarkably well (aided, we are told, by the book's subject buying copies for his friends) and the books on Pavement, Big Star, and Israel Kamakawiwo'ole - who is currently top of the charts in Germany! - have started out strongly, too.

If anyone had told me, when I was putting this all together eight years ago, that the two best-selling titles by late 2010 would be on Neutral Milk Hotel and Celine Dion - that would have made no sense whatsoever. (The rest of the Top 10, if you think about it, is fabulously predictable...)

1. Neutral Milk Hotel

2. Celine Dion

3. Rolling Stones

4. Radiohead

5. The Kinks

6. Velvet Underground

7. The Smiths

8. Joy Division

9. The Beatles

10. Bob Dylan

11. David Bowie

12. The Beach Boys

13. Beastie Boys

14. My Bloody Valentine

15. Led Zeppelin

16. Pixies

17. Pink Floyd

18. DJ Shadow

19. Neil Young

20. Love

21. The Band

22. The Replacements

23. Jeff Buckley

24. Jimi Hendrix

25. Captain Beefheart

26. Sonic Youth

27. R.E.M.

28. Steely Dan

29. The Ramones

30. Black Sabbath

31. Dusty Springfield

32. Magnetic Fields

33. Brian Eno

34. Slayer

35. Nirvana

36. Elliott Smith

37. Minutemen

38. Bruce Springsteen

39. Prince

40. Guided By Voices

41. Tom Waits

42. Elvis Costello

43. Belle & Sebastian

44. James Brown

45. The Who

46. The Byrds

47. Nick Drake

48. Throbbing Gristle

49. Stone Roses

50. U2

51. Big Star

52. Jethro Tull

53. Joni Mitchell

54. Abba

55. The MC5

56. Sly and the Family Stone

57. Patti Smith

58. Afghan Whigs

59. Stevie Wonder

60. Wire

61. PJ Harvey

62. The Pogues

63. Pavement

64. A Tribe Called Quest

65. Flying Burrito Brothers

66. Madness

67. Guns N Roses

68. Israel Kamakawiwo'ole

69. Nas

70. Public Enemy

71. Richard & Linda Thompson

72. Flaming Lips

73. AC/DC

74. Van Dyke Parks

And who could have predicted that a (very, very good) book about Van Dyke Parks would get off to a slow start?

.jpg)

Oh, and if you had to pick a live triple bill, for one night only, of bands/artists who are next to each other on this list, who would you most want to see? Right now, I'd go for a line-up of Springsteen, Prince, and Guided By Voices. That would put Pollard through his paces...

Friday, October 22, 2010

Cultural Catalyst, indeed...

Essential Rock Fiction

Bookslut's Michael Schaub was on NPR's Soundcheck the other day talking about "Essential Rock Fiction." He lists his top 5, too:

1. The Ground Beneath Her Feet by Salman Rushdie

2. Master of Reality by John Darnielle

3. Great Jones Street by Don DeLillo

4. The Exes by Pagan Kennedy

5. The Last Rock Star Book, or, Liz Phair: A Rant by Camden Joy

Thursday, October 21, 2010

Darnielle and Bruno - together again!

John Darnielle (the man behind our heartrending Black Sabbath volume) and Franklin Bruno (author of our fabulous Elvis Costello volume) have reunited to put out Undercard, by the Extra Lens. Full details on the Merge Records site, here.

Wednesday, October 20, 2010

Nine Inch Nails' Pretty Hate Machine - Daphne Carr

The moment you've all been waiting for is here. I present an excerpt from beloved author and blogger Daphne Carr's new 33 1/3 on Pretty Hate Machine. The book will available mid-March and will certainly blow your mind.

Pre-order it from Amazon today and also be sure to check out Daphne's website.

From Daphne Carr:

The Becoming

In 1979 Bruce Springsteen wrote a song called “The River,” a story of a teen pregnancy prompting a loveless marriage in which the father works a crummy job whose future is uncertain “on account of the economy.” If you take Pretty Hate Machine as the sound of that child’s growing up, then the album is not a harbinger of the technofuture but the continued articulation of dread felt by a certain kind of man given certain chances.

Pretty Hate Machine arrived in the final year in office for Ronald Reagan, a fiercely antilabor president whose tax incentives made it easy to close American factories and whose trickle-down economics curbed 1970s inflation while crushing the country’s working people. Reagan’s mantra of personal responsibility focused the blame for lost jobs on workers, and his government cut social programs that could help the newly unemployed, including health care, food stamps, and education. This was the playbook of economic neoliberalism, which would come to be a global strategy to redistribute wealth back to elites.

Reagan’s policies drove the U.S. into the postindustrial era at an enormous human cost. Industrial music was one poetic response to this trauma, much like country music was earlier in the history of industrialization. Country rose as a genre at the moment when most Americans had left rural areas for cities, as a kind of modern music about rural, social, and temporal distance. It was a way to understand the lost connection to the land, along with the humiliations heaped onto working-class, mostly white folks trying to make a decent living. Country musicians have defined themselves against the urban, cosmopolitan, and technologically modern world through recordings that emphasize acoustic timbres and rough vocal qualities. Lyrics idealize the rural, celebrate the pride of manual labor and integrity of a promise, and lament the singer’s or others’ actions when they fail to live up to an ideal or “sell out” for the modern.

Industrial is a postmodern music about the failures of modernity, a genre begun as an avant-garde practice in 1970s England but which grew into a network of underground scenes in fading Western industrial cities by the Eighties. The dry irony of Throbbing Gristle’s maxim “Industrial music for industrial people” has been interpreted across the globe by different instruments and musical styles, and with varied lyrical approaches. One thing is constant: industrial musicians embrace the technologies of management, the sounds of the shop floor, and flexible, nonlinear production techniques in their critique of power. Their cut-ups, sputtering drum machines, and shreds of harsh noise are the ugly mirrors of pop music’s technological wonderland, while their lyrics literalize the horror of humans’ being treated as dead machines in pop-Marxist language and production styles that robotize the voice. Like the sci-fi traditions it samples so heavily, industrial posits a central theme: dystopia is already around us, if only we were awake enough to see it. The music becomes a way for its listeners to stay sharp, to hear and feel not sorrow for the betrayals that have led to their lost way of life but to see causes, feel rage, and be moved to resistance.

Nine Inch Nails borrow the sound and style of electro-industrial but reject the overt politics and parody of the subgenre to focus almost exclusively on the personal tragedy of the people and institutions that fail one individual: Trent Reznor. NIN’s lyrics explore the repressions of religion, family, and society, but only as they pertain to one life, sung in almost too-human melodies and without perceivable irony. With Nine Inch Nails, the effects of mechanization are laid bare: the human experience of powerlessness in postmodern, postindustrial life is crystallized by someone screaming in and against an impossible room full of synthesized sensations.

A generation of young men and women had sympathy for such a sound. Dead-end job, no health care, apocalyptic faith, broken family. They wanted to switch off entirely, but there was one nagging problem: they were still human.

Crooning melodies and sweet pop hooks were Reznor’s major sonic crimes against 1980s industrial music. Another was this focus on the personal, the absence of real politics. That Reznor subsumed industrial’s clangs, grinds, and warps into pop and sold millions of records only made the case against NIN worse. It is possible to hear Nine Inch Nails as the watering down and commodification of industrial’s anticapitalist musical subculture, but for the majority of people slumbering through Reagan’s American morning, Nine Inch Nails was a stunning revelation: dissent from the complacence of suburbia was possible, and it could sound so strange.

Other mainstream alternative bands of the 1990s inspired similar awakenings, but none so bluntly addressed the undersides of religion, power, sexuality, corporeality, and trust as did Nine Inch Nails. Take, for instance, the band’s most famous song, “Closer.” It’s a six-minute pop hit built from the kick of Iggy Pop’s “Nightclubbing,” with an inhuman metronome, a queer synth hook, and distant distortion that builds into the lyrical confession that only the least human of intimacies is tolerable for he who feels vile, broken, fallen—that only through carnality can he experience something like salvation. After all the hard drums, synths, and lyrics, the song ends with a naive keyboard hook.

Tenderness and brutality: Reznor has veered between the two throughout Nine Inch Nails’ career. This can be seen best in his approach to the keyboard—in his legato fingertips and in his fist. As a child, Reznor distinguished himself on the piano, and was encouraged by his teacher Rita Beglin to study music for a profession. He showed a fondness for works with long legato lines, such as those of Frédéric Chopin and Erik Satie. Practicing this style of French salon music, he would learn to press a key with constant energy, to linger with patience and release only after the next finger connected. The last key of a phrase in this style is a slow release into nothingness. These scores demand incredibly tender phrasing, as the player’s fingers mimic the breath of an anguished singer. But from the first moment of NIN, Reznor beat the hell out of his keyboards. As he grew wealthier and the stage shows larger, more keyboards and guitars joined the heaps that roadies glue together after gigs. His mission was to focus the energy of this European parlor instrument turned tone trigger into an aggressively masculine form of expression. Turning synths tough was part of Reznor’s artistic achievement: he dramatized the expressive qualities of the machine for the purpose of sounding human. The trick of Nine Inch Nails is to make synth-pop sound like hard rock through gesture, distortion, and banks of noise.

But in the Hate Machine era, the music was still pretty synth and pretty pop.

Home Recording Contest Update #2

The judges have been asked to rank the top 10 songs in order of preference, so that each judge's #1 pick will receive 10 points, #2 pick receives 9 points, and so on down the line. The points totals from all 7 judges will then be tallied and we'll get in touch with the winners and post the songs here on the blog.

In the meantime, check out the AC/DC contest running now, as well as excerpts from upcoming books in the series (Radiohead, Slint, Nine Inch Nails).

Monday, October 18, 2010

Silence!

All of which leads to the best excuse I can possibly think of to post this clip from 2001's Pootie Tang:

Sadatay!

AC DC's Highway To Hell - By Joe Bonomo - plus an exciting contest!

Just in case you missed this one back in May, below is an excerpt from Joe Bonomo's fabulous look at Highway to Hell. Available from the Continuum website and amazon now!

Don't have the cash for the book at the moment?

I've got a lovely copy sitting on my desk with your name on it. And....Joe Bonomo has graciously offered to personalize a book for the winner.

The rules for this contest are simple: Why do you love (or hate) AC DC in 500 words or less.

Go wild, images encouraged. Deadline: Monday, November 8th.

Email submissions to me at agrossan@continuum-books.com

The winner will receive a free copy of the book and have his/her entry posted on this here blog!

Here's an excerpt from Joe Bonomo:

Six years after Highway to Hell was released, Richard Ramirez was apprehended in Los Angeles. Between June of 1984 and August of the following year, Ramirez had murdered and raped sixteen people in the L.A. area, often leaving behind a sick signature of scrawled demonic ciphers, including a pentagram. Los Angeles police stated that Ramirez was a self-described fan of AC/DC, wore AC/DC t-shirts, and at the grisly scene of one of his violent sprees left behind an AC/DC cap. Allegedly, Ramirez’s favorite song was “Night Prowler,” the final track on Highway to Hell.

A haunting, haunted slow-blues, the six-and-a-half minute “Night Prowler” is remarkable for a number of reasons, not least of which is the controlled, vivid band performance in which Angus reaches deep into his love of blues-styled playing and offers affecting, evocative playing. An eerie crawl in 6/8 with the guitars tuned a half-step down, the closer colors in an unsettling way what comes before it. The tune begins with a sharp intake of breath, three chords that outline the music’s dark terrain, and then a tumble into the band performance held aloft by a long, sustained note by Angus that nearly perishes on the strings. Before Bon begins singing, the mood has been established: foreboding, fearful, and dark. Ten years earlier to the month (and only a few miles away) the Rolling Stones had recorded “Midnight Rambler,” a slow-blues similar to “Night Prowler” in its menace and lurch. Some see the Stones’ classic as an influence on Bon and the Young brothers; both songs begin and end in the source material of the blues, Malcolm and Angus’ first love. “Anyone can play a blues tune,” Angus noted to Vic Garbarini, “but you have to be able to play it well to make it come alive. And the secret to that is the intensity and the feeling you put into it.” He adds, “For me, the blues has always been the foundation to build on.”

One of the few songs by other artists that AC/DC would cover was Big Joe Williams’ standard “Baby, Please Don’t Go,” issued as the first song on their debut album in 1975. The guys likely dug Big Joe’s biography: he was a belligerent, itinerant bluesman who spent his formative years in the Delta as a walking musician who played work camps, jukes, store fronts, and streets and alleys from the South through the Midwest. Williams was a hard-working, highly unique and ramshackle kind of player who favored a funky nine-string guitar and a jerry-rigged, homemade amp. The brash and confident punks in AC/DC certainly favored what historian Robert Santelli describes as Williams’ “fiercely independent blues spirit.” The chugging “Baby, Please Don’t Go” became a favorite for Sixties and Seventies rock & roll bands to cover, extend, make their own. Williams’ 1935 version is acoustic mania; critic Bill Janovitz notes that “the most likely link between the Williams recordings and all the rock covers that came in the 1960’s and 1970’s would be the Muddy Waters 1953 Chess side, which retains the same swinging phrasing as the Williams takes, but the session musicians beef it up with a steady driving rhythm section, electrified instruments, and Little Walter Jacobs wailing on blues harp.”

AC/DC loved it. Their take on Muddy’s take of Big Joe’s lament was immortalized in a version broadcast on ABC’s (Australian) Countdown in April of 1975. The band seems to be having a blast with the galloping number, Angus and Malcolm running up and down their frets with a delinquent’s glee, but the kicker — of course — is Bon: he comes onstage dressed like a demented Pippi Longstocking, complete with a short skirt, blonde pig-tails, dark lipstick, and blue eye-shadow. During the solo breakdown, he stands next to Angus and theatrically lights a cigarette, and Pippi’s knee-sock innocent turns into the whore dear to Bon’s heart. Watch Rudd in the video: he can’t keep from laughing at the spectacle.

The blues in “Night Prowler” is slower, sexier, much more sinister than Big Joe’s, and no less indebted to the tradition within which the band has always worked. (I would have loved to have heard John Lee Hooker moan and turn it inside-out.) The tale of a shadowy stalking, though packed with narrative details, wouldn’t have won Bon a Pulitzer. The images in the first verse are hoary, well worn: the full moon; the clock striking midnight; the dog barking in the distance; a rat running down the alley. But Bon’s howling delivery — fully committed, and trusting the time-honored appeal of a dark night’s eeriness — sends tremors throughout the song. Because he believes this stuff, now so do we. The imagery in the second verse is more intimate; we’re in the girl’s bedroom now where she’s preoccupied and scared to turn off the light, fearing noises outside the window and shadows on the blind. Anticipating the second chorus, the verse ends with the singer slipping into her room as she lies nude, as if on a tomb. What’s going on here? Autobiography, or a spec script for a slasher movie? A little of both, likely, given Bon’s personal history and juicy imagination. He sings in the end that he’ll make a mess of her, and I always disliked the line; it adds explicit violence to a scenario that at the fork of fantasy and reality could’ve gone either way. Bon felt that it added to the mise-en-scène, I guess, or he was honestly owning up to hostile tendencies inside himself. Most likely, he was giving his listeners vicarious thrills on the dark side, what they wanted all along.

I didn’t want it. I hardly listened to “Night Prowler” after I bought the album, though I liked the slow burn of the band’s playing and how Angus’ soloing added a voice to the song. The song scared me a little, and I resented having to like a song that I disliked because it’s on a great rock & roll album. Richard Ramirez admitted to loving “Night Prowler” to the point of heinous identification, in part prompting L.A. media to dub him the “Night Stalker,” a nickname that will last in perpetuity. My friends and I rolled our eyes when we heard Ramirez’s story: another nut job trying to use rock & roll as an excuse, as a defense. I remembered years earlier watching The Dukes of Hazzard on television and marveling at the fifty-foot jumps that Bo and Luke would make in the General Lee in some hilly Georgian county. The moment that I belted myself into a Chevy Chevette in the high school parking lot for my first driver’s-ed lesson, I intuited Damn, this thing weighs a ton, and the disconnect between fantasy and actual life was made pretty clear. Ramirez didn’t or couldn’t make such a distinction, and because of that, the closing song on Highway to Hell will be forever linked to a homicidal maniac who tragically took sixteen innocent lives in brutal ways.

When news of Ramirez’s comments made its way into the insular AC/DC camp, the band recoiled, claiming that Ramirez wildly misunderstood the song: it’s just about a horny guy sneaking into his girlfriend’s bedroom at night, innocent, hormonal, high school stuff. Yet Bon Scott’s more treacherous imagery pushes the song into regrettably mean places. I’m not sure that the band can have it both ways.

A typically winsome gift from Bon himself ultimately rescues “Night Prowler.” In the closing moments, as the chords wane, Bon utters under his breath a weird, nasal phrase that I couldn’t figure out at the time. (What is that, some bizarre Aussie mantra?) Eventually I learned that he’d said, “Shazbot, Na-Nu, Na-Nu.” As AC/DC were recording in the Spring of 1979, Mork and Mindy was ranked third in American television Nielson ratings; Robin Williams’ interstellar character from the planet Ork was invading living rooms and rec rooms at a happy rate, and Bon was watching. “Na-Nu, “Na-Nu” was an Orkan greeting; “Shazbot” an Orkan curse. Maybe that’s what appealed to Bon: at the end of the band’s best album he gets to say hello and swear at the same time, channeling his inner alien. It’s testament to the band’s sense of humor that they kept the aside on the album. It’s a perfect way to send up the danger and fear lingering after “Night Prowler.”

The album ends with a joke, the final words from by Bon Scott on an AC/DC album. Shit! Hello! Perfectly weird.

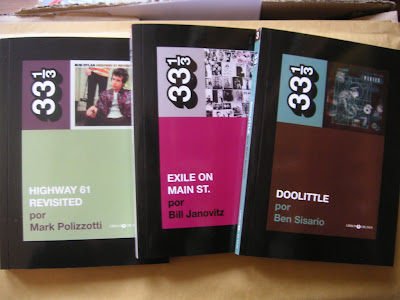

33 1/3 in Spanish, at last!

They're being published by the new book arm of the record label Discos Crudos, and you can learn a little more about them here.

Thursday, October 14, 2010

Tuesday, October 12, 2010

Slint - Spiderland by Scott Tennent

We are very pleased to announce this fantastic addition to the series...out in November

We are very pleased to announce this fantastic addition to the series...out in NovemberFrom the back cover...

"Of all the seminal albums to come out in 1991—the year of Nevermind, Loveless, Ten, and Out of Time, among others—none were quieter, both in volume and influence, than Spiderland, and no band more mysterious than Slint. Few single albums can lay claim to sparking an entire genre, but Spiderland—all six songs of it—laid the foundation for post rock in the 1990s. Yet for so much obvious influence, both the band and the album remain something of a puzzle.

This thoroughly researched book is the first substantive attempt to break through some of the mystery surrounding Spiderland and the band that made it. Scott Tennent has written a long overdue look at this remarkable album and its origins, delving into the small, insular musical universe that included bands like Squirrel Bait, Maurice, Bitch Magnet, and Bastro. The story, helped by in-depth interviews with band members David Pajo and Todd Brashear, explores the formation of Slint, the recording of Tweez, and the band’s dramatic move into the sound of Spiderland."

A little taste of what's inside from Scott Tennent...

The accepted story of Slint’s origin winds back to Squirrel Bait and usually ends there, as if the notion that Brian McMahan and Britt Walford shared the stage with fellow godfather of post-rock David Grubbs was too mythic to contest. But to trace a straight line from one band to the other is to overstate the significance of Squirrel Bait at the expense of the intertwining relationships and lesser-known bands shared by each of the young men who ultimately created Spiderland. Squirrel Bait is but one thread among many.

It’s certainly not the first thread. To pick that up you’d need to travel back to J. Graham Brown Elementary School, Grade 6, 1981. Founded ten years earlier, the Brown School was (and is) notable for its open, unstructured learning environment. The arts were heavily emphasized and each student’s curriculum was individually molded based on their unique aptitude, interests, and self-discipline. “I think [Brown] was pretty significant for all of us,” Brian McMahan told Alternative Press in 2005 — “all of us” being he and his classmates, Britt Walford and Will Oldham. “I don’t think I would’ve been so involved in music or writing if I hadn’t gone there,” he said. Just eleven and twelve, respectively, McMahan and Walford had already picked up instruments; Oldham was musically inept, but his older brother Ned, an eighth-grader, played bass. So Brian, Britt, and Ned, along with friends Stephanie Karta and Paul Catlett, started a band. They were called the Languid and Flaccid, and were an “art/noise band,” according to Clark Johnson, then a high school freshman who saw some of the band’s shows. “They were just little kids,” Johnson recalled in a 1986 interview in a small Xeroxed zine called the Pope. “They had songs like ‘White Castles’ and ‘Fire Engine,’ then they also had songs like ‘K Song,’ ‘L Song,’ ‘M Song,’ ‘N Song,’ etc. Their best song was called ‘Big Pussy,’ and it was so good. Brian sings on it way before his voice changes . . . Yeah, Languid and Flaccid were great.” Sean Garrison, a young Louisville punk, was also a fan. “Languid and Flaccid were a very garage-y band,” he told me. “Very clever . . . slightly smart-assed. It was just amazing hearing these guys. Man, they could play.”

Most tween bands tend not to justify their place in the annals of indie rock history, if only because they seldom make it off of the playground and onto a bona fide stage. But the Languid and Flaccid played out, holding their own against the other, older bands in the scene like Your Food, Malignant Growth, and the Endtables. All-ages venues at the time were scarce, so the Languid and Flaccid would get on Sunday matinee bills at a dingy downtown dive called the Beat Club. Garrison, known around town as Rat, first caught them at a Beat matinee. He was fairly new to the scene; he’d gotten involved because his friend, Brett Ralph, had recently become the new singer for Malignant Growth, arguably the biggest punk band in town. Just fourteen himself, Garrison became immediately compelled to check out this band of twelve-year-olds who had a set’s worth of all original music. So he made his way to the Beat Club to see the Languid and Flaccid open for Your Food on Halloween 1982.

“There was this little seedy pocket in Louisville then,” he told me. “The Beat Club was next to a really scary strip club — you couldn’t get seedier than this — called the Penguin. It was serious.” The Languid and Flaccid boys would get dropped off by their parents, who would help them load their equipment into the dank and dirty club populated by the intimidating punks who were part of the Louisville scene. “The guys that were in bands back then, some of them were really scary. Really scary. And some of them got scarier. But those kids could hang. It was very, very impressive, at least to me. It blew my mind.”

*

It was on the exact same day — Halloween 1982 — that Clark Johnson and his childhood friend David Grubbs kicked around the idea of starting their own band. The two sophomores were loafing around listening to records when Grubbs piped up out of nowhere, “Why don’t you play bass?” So Johnson picked it up. The two didn’t actually start practicing until December; they had to wait for their drummer, a friend named Rich Schuler, to come home from his first semester at University of Cincinnati, and Johnson didn’t own his own equipment until the following year. It wasn’t serious anyway: they named the group Squirrelbait Youth, in simultaneous emulation and parody of the DC hardcore scene, not to mention the local bands who were aping the anti-authoritarian rage with all the suburban naïveté they could muster. “Our first song was ‘Tylenol Scare,’ right after the Tylenol thing. And ‘That Badge Means You Suck,’ things like that,” Johnson told the Pope. Most of the energy put into Squirrelbait Youth was in concept — it was more of an inside joke between Johnson and Grubbs, mocking the local punk scene. Besides, Grubbs was in a more serious band at the time, a new wave group called the Happy Cadavers. They had just self-released their debut 7”, With Illustrations. “Grubbs was not taking [Squirrelbait Youth] seriously at all and not putting any time into it,” said Johnson. But the Happy Cadavers soon dissolved, and Johnson pressed Grubbs into putting more stock into their venture. “We dropped the ‘Youth,’ and I bought a bass.” It was impossible to be more serious, though, when their drummer could only practice on spring break and winter and summer vacation. They needed to find a replacement.

*

By late 1982 the Languid and Flaccid had already been around for more than a year, and Walford, McMahan, and Oldham were growing up and growing restless. They wanted to make music that was louder, faster, more aggressive. So they started a second band which they dubbed Maurice. Rat, who had become utterly enamored with the Languid and Flaccid, saw an opportunity to ingratiate himself into the new act. “I just kind of pushed my way in. They didn’t need [a frontman], I just insisted they did. I was like, ‘Man, I’m doing it.’”

If their intent was to create a more aggressive band, then the addition of Rat was a coup. “My level of rage was so much higher than theirs, it must have seemed comical. Just like their lack of rage sometimes seemed comical to me,” Garrison recalled. “Back then I didn’t realize that the angst or the fury I had, it definitely wasn’t teen angst. I was way beyond that.”

Indeed, Rat’s background could not have been more different from that of his bandmates. Walford, McMahan, and Oldham all grew up on Louisville’s East End, a middle-class and upper-middle-class part of town filled with tree-lined streets and well-kept lawns. As evidenced by the boys’ enrollment in the Brown School, their parents viewed their children’s potential as unlimited. They encouraged their kids to learn music, literature, and art. None of this described Rat’s childhood. Louisville’s South End was a more working-class, blue-collar part of town — and Rat lived south of there, in Pleasure Ridge Park, twenty miles beyond what was then the city limits. His father was an ex-marine who worked at the local ironworks. “I come from a family where if you didn’t have a dangerous job and you didn’t bust your ass, then you were a pussy.” The danger of daily life was no exaggeration — Garrison’s father, like his grandfather, died on the job. Garrison launched himself out of his home and out of his neighborhood like a juggernaut, plowing his way into the Louisville punk scene. He landed in Maurice, where his shrieking caterwaul both compelled and alienated audiences — and his bandmates.

Saturday, October 09, 2010

Wowee Zowee book reviewed

The whole review is worth reading (and you can do so here) but I particularly like this part:

"Bryan Charles' Wowee Zowee is a perfect example of why the 33 1/3 series is so successful and has had such long legs--with every volume there is the chance at greatness. Not every volume is great, and a few are downright boring, but Charles' sharp writing, self-referential framework, and measured earnestness make his book one of the series' biggest successes, and a great piece of rock journalism."

That "chance at greatness" is something I've always wanted the series to have - of course, it doesn't always work out like that, but giving the authors as much freedom as possible, trying dozens of different approaches to writing about music...these still feel like valid things to be doing, 7 years after the series started.

This would also seem an opportune moment to mention Bryan's about-to-publish memoir, There's a Road to Everywhere Except Where You Came From. About which, people are already saying very nice things:

“A sneakily disturbing, disarmingly profound, casually devastating memoir, taut and adept, that cracked me up even at its saddest moments, and broke my heart almost without my quite noticing.”

—Michael Chabon

"This is the book I can't forget...Full of insightful, transcendent regular-guy moments and bad decisions, it didn't make me like the author, but it knocked me on my ass."

—Library Journal (starred review)

“With ease and humor, Bryan Charles does what all writers aspire to do: he shows us the familiar in a whole new way. His beautiful, often painful, honesty makes the inside of his head a fascinating place to be.”

—Rachel Sherman, author of The First Hurt and Living Room

Thursday, October 07, 2010

Radiohead - Kid A, By Marvin Lin - An excerpt

The publication date is fast-approaching. Here's a taste of what's to come...

Pre-order the book from our website here, and set your iphone countdown app to November 25th.

EXCERPT:

On December 12, 1920, artist Tristan Tzara wrote a manifesto on behalf of the international cultural movement called Dada. Divided into 16 parts, Tzara’s manifesto contained mostly illogical but occasionally incisive prose, vacillating between the odd (“I prefer the poet who is a fart in a steam-engine”) and the odder (“the page was taken to the barbaric country where humming-birds act as the sandwich-men of cordial nature”). But there was one section that stuck out: wedged between a rant on “selfkleptomania” and another on autobiographies “hatching under the belly of the flowering cerebellum,” Tzara, in his most lucid state, provided instructions on how to make a Dadaist poem:

● take a newspaper

● take a pair of scissors

● choose an article as long as you are planning to make your poem

● cut out the article

● then cut out each of the words that make up this article and put them in a bag

● shake it gently

● then take out the scraps one after the other in the order in which they left the bag

● copy conscientiously

● the poem will be like you

● and here you are a writer, infinitely original and endowed with a sensibility that is charming though beyond the understanding of the vulgar.

With the last line, Tzara hoists the poet atop a pedestal as a unique but misunderstood personality. The joke, of course, is that the preceding instructions almost entirely remove personality from the process: can a poet truly be considered “original” in the context of randomness, chance, and appropriation? Here, the artist is held accountable for technique, not for any autobiographical connotations, with the Dadaist poem sharing more aesthetic traits with auto-generated spam emails than with labored-over sonnets flaunting perfect semicolon placement. With a playful sense of irony and wit, Tzara was really critiquing the notions of celebrity, uniqueness, and craft, providing a subversive getaway authors could use to create distance between themselves and their work.

Ninety years since these instructions were first published, the Dadaist poem is still relevant to the silly mythologies we have of the modern musician: original, full of personality, and of course misunderstood.

* * *

So what about Thom Yorke?

While he’s decidedly full of personality, he’s certainly not winning any awards for affability. In a Kid A-era interview with the Observer, he admitted to still receiving hate mail from fans he upset during the OK Computer tour (one letter said it was a pity Jeff Buckley died instead of him), and during the Kid A recording sessions he posted on Radiohead’s official website, “I got beaten up in the middle of Oxford last week by someone who recognized me and saw me as an easy target.” Just try to find an interview with Thom that isn’t prefaced with a jab at his personality. Everyone seemed to have an opinion, and they were often high profile too: Kelly Jones of the Stereophonics called him a “miserable twat”; Noel Gallagher said he was a “cunt”; and Ronan Keating of Boyzone not only called him a “muppet” but also said he’d love to throw him off a mountain (metaphorically). At 2009’s 51st Annual Grammy Awards, Kanye West “sat the fuck down” during Radiohead’s performance after supposedly being snubbed by Thom, while Miley Cyrus claimed she was going to “ruin [Radiohead]” and “tell everyone” after the band refused to have a “sit down” with her. (Perhaps Cyrus should’ve had a “sit down” with West since he “sat the fuck down” anyway.)

And these are only the criticisms that made headlines.

Thom is clearly no stranger to having his personality stretched out and laid bare, but nowhere was this character examination more overblown than during OK Computer’s “Running From Demons” world tour. The press wasn’t concerned with the album’s commentary on the speed of human interaction in a hyper-capitalist technological landscape. It wanted to get to know him, as if the lyrics were purely autobiographical, as if they came from a tortured artist, a visionary, a depressed outcast on the brink of self-destruction who — hey, what do you know — just so happened to be artistically “brilliant.” How many times have both Radiohead’s music and Thom been described as “moody”? How many times have both been described as “paranoid”? To many, including me, OK Computer’s lyrical content and Thom’s psychology were one and the same.

But, ironically, not only were OK Computer’s lyrics overtly skittish but also they were purposefully designed to stray from The Bends’ introspection and to function more like Polaroids. As Thom told Q magazine in 1997, “It was like there’s a secret camera in a room and it’s watching the character who walks in — a different character for each song. The camera’s not quite me. It’s neutral, emotionless.”

However, Thom’s intent with OK Computer was immaterial to an industry that masqueraded as “neutral” and “emotionless.” As depicted in Meeting People Is Easy, the indelible 1998 documentary directed by Grant Gee, the media’s insistence on marketing a downtrodden yet noble artist in fact engendered the very conditions of alienation, disconnection, and simulacrum that OK Computer was lambasting, kick-starting a vicious downward spiral: Why is Thom wallowing in despair? Why is he always so angry? Perhaps it stems from the lingering trauma due to his drooping eyelid? Thom’s aversion to celebrity culture was mistaken for misanthropy, and the journalistic cheap shots aided in part to a nervous breakdown after OK Computer. He had trouble even speaking. As Thom admitted in a Rolling Stone interview,

"I came off at the end of that show, sat in the dressing room and couldn’t speak. I actually couldn’t speak. People were saying, 'You all right?' I knew people were speaking to me. But I couldn’t hear them. And I couldn’t talk. I’d just had enough. And I was bored with saying I’d had enough. I was beyond that."

The industry, as it tends to do, reduced Thom to a manufactured personality, to the point where fictitious storylines seemed to coalesce out of thin air, where consumers could hardly separate the value/function of the band from any other packaged goods on the shelf.

But as the lens focused more vigorously on his personality, Thom was already devising ways to increase the distance.

* * *

It wasn’t surprising, then, when I discovered that Radiohead had actually posted Tzara’s instructions for a Dadaist poem on their official website in the fall of 1999, roughly a year before Kid A’s release. It also wasn’t surprising to find out that Thom in fact employed a similar poem-making technique during the Kid A sessions to combat a two-year case of writer’s block. As he stated on a Dutch television show,

"What I’d went off and tried to do with the writer’s block thing was just basically have all the things that didn’t work and stopped throwing them away, which was what I’d been doing before, and keeping them and cutting them up and putting them in this top hat and pulling them out."

If one of the benefits of the Dadaist poem is the removal of personality and the distancing it provides, then randomly drawing cut-up lyrics from a hat seems like a reasonable reaction. With this new lyrical technique — influenced in part by David Byrne’s like-minded approach to Talking Heads’ Remain in Light — Thom was able to mount a critique that couldn’t be mistaken as autobiographical, couching his lyrics in obfuscation and ambiguity in order to distance himself from rock’s self-important mythologies. It was a lateral technique that provided links, however tenuous, to Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies, to John Cage and the I Ching, to Guy Debord’s Mémoires. “The vocal parts are really interesting,” said guitarist Ed O’Brien, “because it’s the first album that we — as a band — haven’t been aware of what Thom’s singing about. He didn’t talk about his lyrics.”

-Marvin Lin

Wednesday, October 06, 2010

Terry & James & Carl & Celine

You can read a little more of the backstory between Carl's book and Mr. Franco here.On his time on General Hospital

"I'd been discussing the idea [of doing a soap] with this artist named Carter. He's a friend of mine, and I collaborate on different projects with him. We were going to do a movie called Maladies that he was going to direct and I was going to star in, and I was going to play a character who was formerly on a soap opera. And that got us talking about, what if I actually was on a soap opera? Wouldn't that be interesting? People would be surprised. Nobody would expect it. And also, it's a different kind of entertainment and acting and yeah, people often look down on soap operas as kind of inferior entertainment. But I was thinking in a different way at that point.

I had just read this book by Carl Wilson ... about Celine Dion. And he wasn't a fan of Celine but he decided he was going to investigate why. Why does he feel superior to Celine's music? And he didn't come to any definite conclusions, but he figured out that Celine's music means something to some people and gives a lot of people strength, hope — whatever you get from music. So he decided to suspend his judgment and stop looking down on Celine just because she doesn't speak to him. So that's kind of the mindset I was in at that time."

Monday, October 04, 2010

More Dylan in France, plus forthcoming items

Also, Michael Gray will be hosting, in November, further Dylan-themed weekends at his home in the beautiful French countryside. Details:

Dylan expert and critic Michael Gray, who writes the long-running blog The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, is opening his home in France for Dylan Discussion Weekend Breaks this November.

A maximum of six guests per weekend join the author of "Song & Dance Man III", "The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia" and “Hand Me My Travelin’ Shoes: In Search of Blind Willie McTell”, for evenings discussing Dylan’s work, augmented with good local wine and Dylan tracks from Michael’s own collection, after enjoying excellent meals created by his wife, the food writer Sarah Beattie.

Guests can choose topics such as Dylan & the Blues; Dylan & Rock’n’roll; Dylan's Use of the Bible; Dylan, Plagiarism & Bootlegs; Dylan & Literary Culture; Dylan In Concert; Dylan On Film; Dylan & the Beats.

The house is in rural Southwest of France, 45 miles from the Pyrenees and the Spanish border. These weekends follow successful previous breaks for fans sharing their enthusiasm for Dylan’s work in February-March, June and September.

Further details can be had here.

Home Recording Contest Update

Keep 'em coming!