Just a reminder that you now have exactly a month to submit an entry for our writing contest - if you're under 21 years of age. The winning essay will appear in our forthcoming book 33 1/3 Greatest Hits, Volume 1 - publishing in October. We've had a handful of entries already, but it would be great to get some more.

And remember, aside from getting published in our anthology book, the winner gets $250 as well. Life doesn't get much better than that.

If you're too old (trust me, I know how it feels), perhaps you know someone who might want to take a crack at this...

The rules:

1. You must be under 21, as of June 30th this year.

2. You can write up to 2000 words about any album, apart from the 20 albums featured in the book:

Dusty in Memphis

Forever Changes

Harvest

The Kinks Are The Village Green Preservation Society

Meat is Murder

The Piper at the Gates of Dawn

Abba Gold

Electric Ladyland

Unknown Pleasures

Sign 'O' the Times

The Velvet Underground and Nico

Let It Be (Beatles)

Live at the Apollo

Aqualung

OK Computer

Let It Be (Replacements)

Led Zeppelin IV

Exile on Main St.

Pet Sounds

Ramones

3. You can write these 2000 (or less) words in any way you want to - straight essay, lurid prose, verse, humour, fiction, screenplay: I don't mind.

4. Your entry does not need to refer to the 33 1/3 series in any way: it should be a stand-alone piece of writing, that we'll publish as the 21st chapter of this book.

5. You should send it to me, via email, as a Word file, by June 30th. We'll pick a winner by the end of July.

A blog about Bloomsbury Academic's 33 1/3 series, our other books about music, and the world of sound in general.

Wednesday, May 31, 2006

Tuesday, May 30, 2006

Franklin on Grant

Franklin Bruno, author of our excellent Elvis Costello book, has written one of the best pieces I've read so far about Grant McLennan. The piece, on Moistworks, comes with 4 songs to download, and you can link to it here. But here's the main text of it, without the MP3s.

***

As many readers already know, Grant McLennan, who co-founded and co-led The Go-Betweens with Robert Forster from 1978 to 1990 and, in their second incarnation, from 2001 until two weeks ago, died in Brisbane on Saturday, May 6th, at the age of 48. He had been making preparations for a party that evening, complained of not feeling well, went to bed, and never woke up. In the brief interval since the news appeared on the band's official website, nearly 1,500 fans and friends have posted condolences and tributes to the site's message board. Many are from fellow musicians, ranging from Luke Haines (of The Auteurs, whose debut album New Wave is audibly indebted to The Go-Betweens mid-'80s recordings) to Bikini Kill's Tobi Vail. As for me, not just my musical endeavors but probably my personal life would be unimaginably different if not for the 20-plus year relationship I've had with The Go-Betweens' music, so I'm grateful to Alex for inviting me to contribute this note.

In 1977, McLennan was a film-and-literature-obsessed arts student who had never played guitar; he first picked up the bass to learn the songs that the slightly more seasoned Forster had begun writing. (He switched to guitar when the band became a quartet.) But he quickly found his feet as a songwriter: from 1981's Send Me a Lullaby to last year's Oceans Apart, every Go-Betweens full-length was evenly split between the leaders' compositions. In fact, he eventually emerged as the more prolific partner: during the band's 11-year hiatus, he released four solo albums, including the 17-song double-disc Horsebreaker Star, and collaborated on two with The Church's Steve Kilbey as Jack Frost. When he wrote about romantic entanglements, it was with a freshness and specificity that the term "love song" doesn't quite capture. (You could say this of Forster's songs as well.) McLennan's autobiographical songs, evoking his fatherless childhood on a farm in Queensland ("Cattle and Cane," "Unkind and Unwise," "The Ghost and the Black Hat"), were utterly his own, not merely in their subject matter, but in their unconventional, unforced rhythms. In recent blog entries, here, Kilbey recalls the insights into McLennan's methods he got from their writing sessions: "he's got all his songs/written out in one big exercise book/that he musta had since high school...when I first met him grant said he had/thousands of songtitles ready to go." Making songs, it seems, had become one of McLennan's primary ways of responding to the world.

In picking a handful of McLennan songs from the dozens that have been in my head for the last two weeks, I have to begin with the first one I ever heard. "Just A King In Mirrors" is one of his two b-sides to "Part Company," from a 12" single bought at Claremont's Rhino Records in, I think, 1985. (The other, "Newton Told Me," is a cryptic number based on the chord progession to "Lay, Lady, Lay." I have no doubt that McLennan, an avowed Dylan nut, knew this.) I had never so much as heard of the group - and certainly wasn't aware of the awful "critic's band" label they labored under for so many years. I was drawn to their absence from Bleddyn Butcher's cover photo (the skylight of what might be a rural train station, or a sheep-shearing barn), to the uninflected, un-"rock" plainness of their name (I'd never heard of L.P. Hartley's novel or Joseph Losey's film adaptation), and to the lyrics to the a-side (which are Forster's: "that's her handwriting, that's the way she writes") printed on the back. The sleeve had - still has - a slight tear; it cost me 37 cents. The song itself is a bit of a pastiche, as Go-Betweens songs go: the changes and the barstool-hero portrait, too static to be called a narrative, read as country-influenced. But it's also idiosyncratic: the extra two beats in each line of the verse, the way that the leads trouble the harmony (a trademark of the band's first decade, however the guitar duties were split up), the suspended quality of the brief bridge. And, of course, the vividness of the imagery and even the off-rhymes ("scepter"/"spectre") - all these touches make the song's melancholy feel achieved, like something of its own, rather than a quality read off of genre.

Backtracking slightly, "Near the Chimney" is one of the many early songs left unreleased until 2002's reissues of the band's catalog. This one shows up on the bonus disc to 1983's Before Hollywood (the band's second album, and first masterpiece). Musically, it captures the Go-Betweens at their most oblique and enervated, with McLennan still on bass, Forster doing his best to obscure whatever the original chord progression might have been, and the great Lindy Morrison splintering the beat. It's the sound of a band trying to make every moment of what they do a reinvention - or, perhaps, attempting to fit their pop imaginations to the post-punk manners of the time. It takes a few listens to grab hold, but behind the spikiness - and McLennan's urgent art-rock vocal, so different from the even-tempered half-croon he eventually adopted - there's a vivid, vulnerable, and surprisingly well-formed cheating song: "So this is what it comes to/dressing like spies/he won't sleep where another man lies." The reluctant lover who "comes from the long grass" can only be McLennan himself - the wondering country boy of "Cattle and Cane," still disoriented by the ways of the adult world.

I'd be lying if I said I wasn't frustrated by some of McLennan's later, smoother work: it could sometimes seem as though his formal facility at tying a strum pattern, a sharp opening couplet, and a pleasing chorus hook into something song-shaped could lead to pat results. (I suspect he was also finishing one song so he could start the next, which might, every time, turn out to be the one. I know the feeling.) But all the solo records contain gems ("Haven't I Been a Fool," "Riddle in the Rain"), and reuniting with Forster on the three post-hiatus Go-Betweens albums seemed to rekindle his ambition. "Statue" is my favorite from his half of Oceans Apart, an chorusless Symbolist vignette that finds (as I wrote in a Village Voice review) "the singer struggling to bust through some ice maiden's reserve, to say nothing of his own." The arrangement's au courant programmed opening and lush synth oscillations are a world away from the records above - as well they might be, two decades on - but again, the song's heart lies in a vintage McLennan/Forster rhythm/lead division of guitar labor, and in the pockets of unexplored detail - "the songs of Sacha"? Sacha Distel? - tucked into corners of the lyric.

"Black Mule" first appeared on 1991's Watershed, McLennan's first solo album; this solo acoustic version is the first track from That Striped Sunlight Sound, The Go-Betweens' recent, career-spanning live record, on which McLennan appeared satisfied in his achievement and comfortable in his skin. (This bears mentioning because it wasn't always the case: in the mid-'90s, I saw both Forster and McLennan play dispiriting, ill-attended solo shows on separate occasions at Los Angeles' Luna Park. McLennan's ended with a painfully bitter and accusatory song called "Charlatan," which, to my knowledge, he never released.) By way of closing, I'll let the song tell its own story; if there's one thing McLennan knew, it was the power of small mysteries. His songs were his work, his love, his way of understanding the world's strangeness, and of adding to it. Robert Forster has already said that he will no longer use the name he and his partner appropriated from the book that famously begins: "The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there." The Go-Betweens, as such, are now citizens of that country. McLennan's songs still reside in ours.

- by Franklin Bruno

***

As many readers already know, Grant McLennan, who co-founded and co-led The Go-Betweens with Robert Forster from 1978 to 1990 and, in their second incarnation, from 2001 until two weeks ago, died in Brisbane on Saturday, May 6th, at the age of 48. He had been making preparations for a party that evening, complained of not feeling well, went to bed, and never woke up. In the brief interval since the news appeared on the band's official website, nearly 1,500 fans and friends have posted condolences and tributes to the site's message board. Many are from fellow musicians, ranging from Luke Haines (of The Auteurs, whose debut album New Wave is audibly indebted to The Go-Betweens mid-'80s recordings) to Bikini Kill's Tobi Vail. As for me, not just my musical endeavors but probably my personal life would be unimaginably different if not for the 20-plus year relationship I've had with The Go-Betweens' music, so I'm grateful to Alex for inviting me to contribute this note.

In 1977, McLennan was a film-and-literature-obsessed arts student who had never played guitar; he first picked up the bass to learn the songs that the slightly more seasoned Forster had begun writing. (He switched to guitar when the band became a quartet.) But he quickly found his feet as a songwriter: from 1981's Send Me a Lullaby to last year's Oceans Apart, every Go-Betweens full-length was evenly split between the leaders' compositions. In fact, he eventually emerged as the more prolific partner: during the band's 11-year hiatus, he released four solo albums, including the 17-song double-disc Horsebreaker Star, and collaborated on two with The Church's Steve Kilbey as Jack Frost. When he wrote about romantic entanglements, it was with a freshness and specificity that the term "love song" doesn't quite capture. (You could say this of Forster's songs as well.) McLennan's autobiographical songs, evoking his fatherless childhood on a farm in Queensland ("Cattle and Cane," "Unkind and Unwise," "The Ghost and the Black Hat"), were utterly his own, not merely in their subject matter, but in their unconventional, unforced rhythms. In recent blog entries, here, Kilbey recalls the insights into McLennan's methods he got from their writing sessions: "he's got all his songs/written out in one big exercise book/that he musta had since high school...when I first met him grant said he had/thousands of songtitles ready to go." Making songs, it seems, had become one of McLennan's primary ways of responding to the world.

In picking a handful of McLennan songs from the dozens that have been in my head for the last two weeks, I have to begin with the first one I ever heard. "Just A King In Mirrors" is one of his two b-sides to "Part Company," from a 12" single bought at Claremont's Rhino Records in, I think, 1985. (The other, "Newton Told Me," is a cryptic number based on the chord progession to "Lay, Lady, Lay." I have no doubt that McLennan, an avowed Dylan nut, knew this.) I had never so much as heard of the group - and certainly wasn't aware of the awful "critic's band" label they labored under for so many years. I was drawn to their absence from Bleddyn Butcher's cover photo (the skylight of what might be a rural train station, or a sheep-shearing barn), to the uninflected, un-"rock" plainness of their name (I'd never heard of L.P. Hartley's novel or Joseph Losey's film adaptation), and to the lyrics to the a-side (which are Forster's: "that's her handwriting, that's the way she writes") printed on the back. The sleeve had - still has - a slight tear; it cost me 37 cents. The song itself is a bit of a pastiche, as Go-Betweens songs go: the changes and the barstool-hero portrait, too static to be called a narrative, read as country-influenced. But it's also idiosyncratic: the extra two beats in each line of the verse, the way that the leads trouble the harmony (a trademark of the band's first decade, however the guitar duties were split up), the suspended quality of the brief bridge. And, of course, the vividness of the imagery and even the off-rhymes ("scepter"/"spectre") - all these touches make the song's melancholy feel achieved, like something of its own, rather than a quality read off of genre.

Backtracking slightly, "Near the Chimney" is one of the many early songs left unreleased until 2002's reissues of the band's catalog. This one shows up on the bonus disc to 1983's Before Hollywood (the band's second album, and first masterpiece). Musically, it captures the Go-Betweens at their most oblique and enervated, with McLennan still on bass, Forster doing his best to obscure whatever the original chord progression might have been, and the great Lindy Morrison splintering the beat. It's the sound of a band trying to make every moment of what they do a reinvention - or, perhaps, attempting to fit their pop imaginations to the post-punk manners of the time. It takes a few listens to grab hold, but behind the spikiness - and McLennan's urgent art-rock vocal, so different from the even-tempered half-croon he eventually adopted - there's a vivid, vulnerable, and surprisingly well-formed cheating song: "So this is what it comes to/dressing like spies/he won't sleep where another man lies." The reluctant lover who "comes from the long grass" can only be McLennan himself - the wondering country boy of "Cattle and Cane," still disoriented by the ways of the adult world.

I'd be lying if I said I wasn't frustrated by some of McLennan's later, smoother work: it could sometimes seem as though his formal facility at tying a strum pattern, a sharp opening couplet, and a pleasing chorus hook into something song-shaped could lead to pat results. (I suspect he was also finishing one song so he could start the next, which might, every time, turn out to be the one. I know the feeling.) But all the solo records contain gems ("Haven't I Been a Fool," "Riddle in the Rain"), and reuniting with Forster on the three post-hiatus Go-Betweens albums seemed to rekindle his ambition. "Statue" is my favorite from his half of Oceans Apart, an chorusless Symbolist vignette that finds (as I wrote in a Village Voice review) "the singer struggling to bust through some ice maiden's reserve, to say nothing of his own." The arrangement's au courant programmed opening and lush synth oscillations are a world away from the records above - as well they might be, two decades on - but again, the song's heart lies in a vintage McLennan/Forster rhythm/lead division of guitar labor, and in the pockets of unexplored detail - "the songs of Sacha"? Sacha Distel? - tucked into corners of the lyric.

"Black Mule" first appeared on 1991's Watershed, McLennan's first solo album; this solo acoustic version is the first track from That Striped Sunlight Sound, The Go-Betweens' recent, career-spanning live record, on which McLennan appeared satisfied in his achievement and comfortable in his skin. (This bears mentioning because it wasn't always the case: in the mid-'90s, I saw both Forster and McLennan play dispiriting, ill-attended solo shows on separate occasions at Los Angeles' Luna Park. McLennan's ended with a painfully bitter and accusatory song called "Charlatan," which, to my knowledge, he never released.) By way of closing, I'll let the song tell its own story; if there's one thing McLennan knew, it was the power of small mysteries. His songs were his work, his love, his way of understanding the world's strangeness, and of adding to it. Robert Forster has already said that he will no longer use the name he and his partner appropriated from the book that famously begins: "The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there." The Go-Betweens, as such, are now citizens of that country. McLennan's songs still reside in ours.

- by Franklin Bruno

Thursday, May 25, 2006

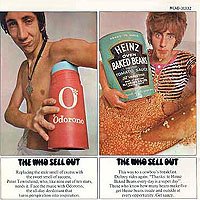

The Who Sell Out

Received a cracking manuscript yesterday from John Dougan, on Sell Out by the Who. We'll be publishing this in September, but here's an unedited preview for you...

***

In 1967, Peter Blake, the most celebrated and successful of the four artists featured in Ken Russell’s Pop Goes the Easel, made a spectacular leap into the world of pop music designing (with his wife, American-born artist Jann Haworth) the dense, allusive cover art for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. At a time when the price tag for album art was about $100, Blake’s frameworthy, gallery-ready effort cost closer to $5,000. It was a work of art surrounding a work of art – at least that’s how Blake, the Beatles, and producer George Martin imagined it – an LP cover that further distanced the (now facially hirsute) Beatles from their pop band beginnings, announcing that a serious artistic statement was inside. Pete Townshend, Kit Lambert, and Chris Stamp envisioned Sell Out having a similar conceptual consistency, one that began with a pop art cover that aggressively and unapologetically celebrated hype – a creative assignment taken on by designers David King and Roger Law. King was a graduate of the London School of Printing and Graphic Arts, and from 1965-1975 was art editor of the Sunday Times Magazine. It was while at the magazine that he developed his trademark technique of cropping photos to accentuate their dynamism, along with the use of processed graphic effects that, according to art critic Christopher Wilson, "gave the magazine a cinematic feel." Cambridge educated Law (who would later go on to international success in the 80s with the political satire puppet show Spitting Image), had been employed as an illustrator for the satirical magazine Private Eye, and contributed political cartoons to the Observer. Sell Out was not his first rock album cover, he’d created the beautifully detailed artwork gracing the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s Axis: Bold as Love. The job of photographing the Who fell to Brooklyn-born expatriate David Montgomery, who would go on to be one of England’s most celebrated portrait photographers, and remains perhaps the only person on record to refer to the Who as acting like "[a group] of very good schoolboys on a day trip."

The finished effort was the opposite of Peter Blake’s gorgeously crafted, somber artistry. Sell Out’s oversized photos, in the pop art tradition of emphasizing advertising’s vulgarity, burst forth from their frames screaming, "Buy this, now!" Townshend, fingers torn and frayed from enthusiastic auto-destruction, clutches a comically outsized container of Odorono, a knowing grin expressing his pleasure at this intensely referential pop art joke. Keith Moon, managing to look contrite and embarrassed, salves an enormous pustule with an equally large tube of Medac (changed to Clearasil in Australia). John Entwistle, his underdeveloped body clad in faux leopard skin, face plastered with an atypically goofy grin, clutches a teddy bear in his left hand, while his right arm cradles a buxom, bikini-clad blonde, in a deft parody of the Charles Atlas workout regimen. (In this particular photo Montgomery references Richard Hamilton’s 1956 pop art collage "Just What is it That Makes Today’s Home’s So Different, So Appealing," wherein a male bodybuilder, itself an idealized image of the postwar American male, clutches a large Tootsie Pop.) Montgomery’s most famous photo, and Sell Out’s most indelible and enduring visual image, is that of Roger Daltrey sitting in a tub filled with Heinz Baked Beans. The messy task was originally to be Entwistle’s but when informed, he deliberately showed up late to the shoot leaving Daltrey, ever the trooper, to fill in. The beans, however, had been refrigerated for some time and, according to legend, Daltrey ended up with a mild case of pneumonia for his efforts.

Accompanying each photo was fake ad copy that read like slightly surreal, imagist poetry ("There used to be a dark side to Keith Moon. Not now. Not any more. If acne is preventing you from reaching your acme, use Medac, the spot remover that makes your pits flit. Put Medac on the spot now."), metaphorically reinforcing the connection between pop art and consumer culture. The combined efforts of King, Law and Montgomery had resulted in a brilliant piece of pop art that, had it been created a decade earlier, would have found a place in Whitechapel Art Gallery or been featured in Ken Russell’s Pop Goes the Easel. The Los Angeles Times, singled it out as rock’s "biggest happening in album covers," declaring it far superior to similar efforts by the Stones, Jefferson Airplane, and even to Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Not everyone, however, saw this audacious cover in quite the same way. Joe Bogart, program director for powerful New York City radio station WMCA, whose charismatic DJs "The Good Guys" (one of whom, Jack Spector, taped a show for Radio Caroline) attracted millions of listeners in the New York metro area, condemned Sell Out as "Disgusting...I won’t even let my children see the cover," and refused to play it. Maybe it was the beans, but Bogart’s overstated outrage was not the Who’s only problem, Decca wasn’t exactly chuffed with the it either.

***

In 1967, Peter Blake, the most celebrated and successful of the four artists featured in Ken Russell’s Pop Goes the Easel, made a spectacular leap into the world of pop music designing (with his wife, American-born artist Jann Haworth) the dense, allusive cover art for Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. At a time when the price tag for album art was about $100, Blake’s frameworthy, gallery-ready effort cost closer to $5,000. It was a work of art surrounding a work of art – at least that’s how Blake, the Beatles, and producer George Martin imagined it – an LP cover that further distanced the (now facially hirsute) Beatles from their pop band beginnings, announcing that a serious artistic statement was inside. Pete Townshend, Kit Lambert, and Chris Stamp envisioned Sell Out having a similar conceptual consistency, one that began with a pop art cover that aggressively and unapologetically celebrated hype – a creative assignment taken on by designers David King and Roger Law. King was a graduate of the London School of Printing and Graphic Arts, and from 1965-1975 was art editor of the Sunday Times Magazine. It was while at the magazine that he developed his trademark technique of cropping photos to accentuate their dynamism, along with the use of processed graphic effects that, according to art critic Christopher Wilson, "gave the magazine a cinematic feel." Cambridge educated Law (who would later go on to international success in the 80s with the political satire puppet show Spitting Image), had been employed as an illustrator for the satirical magazine Private Eye, and contributed political cartoons to the Observer. Sell Out was not his first rock album cover, he’d created the beautifully detailed artwork gracing the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s Axis: Bold as Love. The job of photographing the Who fell to Brooklyn-born expatriate David Montgomery, who would go on to be one of England’s most celebrated portrait photographers, and remains perhaps the only person on record to refer to the Who as acting like "[a group] of very good schoolboys on a day trip."

The finished effort was the opposite of Peter Blake’s gorgeously crafted, somber artistry. Sell Out’s oversized photos, in the pop art tradition of emphasizing advertising’s vulgarity, burst forth from their frames screaming, "Buy this, now!" Townshend, fingers torn and frayed from enthusiastic auto-destruction, clutches a comically outsized container of Odorono, a knowing grin expressing his pleasure at this intensely referential pop art joke. Keith Moon, managing to look contrite and embarrassed, salves an enormous pustule with an equally large tube of Medac (changed to Clearasil in Australia). John Entwistle, his underdeveloped body clad in faux leopard skin, face plastered with an atypically goofy grin, clutches a teddy bear in his left hand, while his right arm cradles a buxom, bikini-clad blonde, in a deft parody of the Charles Atlas workout regimen. (In this particular photo Montgomery references Richard Hamilton’s 1956 pop art collage "Just What is it That Makes Today’s Home’s So Different, So Appealing," wherein a male bodybuilder, itself an idealized image of the postwar American male, clutches a large Tootsie Pop.) Montgomery’s most famous photo, and Sell Out’s most indelible and enduring visual image, is that of Roger Daltrey sitting in a tub filled with Heinz Baked Beans. The messy task was originally to be Entwistle’s but when informed, he deliberately showed up late to the shoot leaving Daltrey, ever the trooper, to fill in. The beans, however, had been refrigerated for some time and, according to legend, Daltrey ended up with a mild case of pneumonia for his efforts.

Accompanying each photo was fake ad copy that read like slightly surreal, imagist poetry ("There used to be a dark side to Keith Moon. Not now. Not any more. If acne is preventing you from reaching your acme, use Medac, the spot remover that makes your pits flit. Put Medac on the spot now."), metaphorically reinforcing the connection between pop art and consumer culture. The combined efforts of King, Law and Montgomery had resulted in a brilliant piece of pop art that, had it been created a decade earlier, would have found a place in Whitechapel Art Gallery or been featured in Ken Russell’s Pop Goes the Easel. The Los Angeles Times, singled it out as rock’s "biggest happening in album covers," declaring it far superior to similar efforts by the Stones, Jefferson Airplane, and even to Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Not everyone, however, saw this audacious cover in quite the same way. Joe Bogart, program director for powerful New York City radio station WMCA, whose charismatic DJs "The Good Guys" (one of whom, Jack Spector, taped a show for Radio Caroline) attracted millions of listeners in the New York metro area, condemned Sell Out as "Disgusting...I won’t even let my children see the cover," and refused to play it. Maybe it was the beans, but Bogart’s overstated outrage was not the Who’s only problem, Decca wasn’t exactly chuffed with the it either.

Wednesday, May 24, 2006

It's also our sales manager Jane's birthday today

I enjoyed David Yaffe's piece in Slate today, reproduced here:

The State of the Dylan Address

An annual tradition.

By David Yaffe

Mr. Speaker, Vice President Cheney, members of Congress, readers of Slate, distinguished Fraysters, fellow citizens. Sixty-five years ago today, our Dylan was busy being born. He's older than that now. As he becomes a contender for the cover of AARP Magazine, it is my duty to report on the state of the Dylan.

It is true that money doesn't talk, it swears. Nevertheless, over the last six years, we have brought new economic growth by investing in our Dylan. According to the Office of Billboard and Budget, the Dylan's last CD of new material, Love and Theft, sold 754,000 copies, and the Dylan made $1 million in royalties from the book Chronicles Vol. 1. Now we move into a new age of technology: the Dylan's iTunes music store and XM Radio's Theme Time Radio Hour, hosted by the Dylan. Add to this the upcoming Twyla Tharp dance spectacle, a Todd Haynes biopic where seven different actors will play the Dylan, a new CD ready to hit stores, Michael Gray's comprehensive and up-to-date Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, and the perennial fact that he's still on the road, headin' for another joint, and it is unassailably clear: My fellow Americans, the state of the Dylan is strong. (Applause.)

Yet we are still, in the words of our founders, striving to form a more perfect Dylan. Anyone following the state of the Dylan will recognize the character in Jonathan Cott's Bob Dylan: The Essential Interviews, published this month. This is the Dylan who eviscerated a Time reporter and immortalized him as the clueless "Mr. Jones" of "Ballad of a Thin Man." The book charts four decades of exchanges: We get the yarn-spinning Dylan of the early '60s, the combative, elliptical drugged-out icon of the mid-'60s, the oracular converso of the late '70s, the embittered burnout of the '80s, the ailing comeback kid of the '90s, and the sexagenarian swami of the 21st century. The Dylan of XM Radio's Theme Time Radio Hour, however, is a Dylan both familiar and startling.

Listening to Dylan's show, we hear the chimes of freedom on the march. Back in 1966, Dylan was still battling uptight forces, even when confronted with the hep Nat Hentoff, who quoted him saying that people "hang out on the radio." Dylan corrected him: "I didn't say that people 'hang out' on the radio, I said they got 'hung up' on the radio." Forty years later, Dylan is definitely hanging out on the radio. There will be, as usual, the nattering nabobs of Dylanology ascribing monumental significance to every utterance he makes, but they would be missing the spirit of the show. Dylan is wisecracking, relaxed, and open on these satellite waves, rasping like Tom Waits' DJ character in Mystery Train. Each show has a theme; so far they've included "Weather," "Mother," "Drinking," and "Baseball." With each theme, Dylan has an excuse to spin records he likes, intone song lyrics like a gnomic bluesman, crack jokes, and reveal minor clues about his influences, such as when he kicks off his first show with Muddy Waters' "Blow, Wind, Blow," a "Blowin' in the Wind" source that bypassed most Dylanographers. On the "Baseball" episode, he even sings "Take Me Out to the Ball Game."

The Dylan, aided by an international coalition of researchers and probably reciting his patter from a tour bus or hotel room, tells a little anecdote about each artist he plays—the more obscure the better. But you can understand every word and, lo and behold, he actually seems to be enjoying himself. "Here's Sonny Rollins, covering all the bases," he rasps, introducing Rollins' "Newk's Getaway," breaking in just before Rollins' solo to interject, "Let's get goin'." By the time he gets to the third episode, "Drinking," he seems light-years away from the stonewalling Delphic oracle we know. The state of the Dylan might actually be getting mellower with age, but he is not in a malaise. Five years ago, when Mikal Gilmore asked him about his history with alcohol, Dylan snapped: "I can drink or not drink. I don't know why people would associate drinking or not drinking with anything that I do, really." But get the man behind the mic, and he'll offer his recipe for a mint julep (after Lenore from Cincinnati asked for it and he played "One Mint Julep" by the Clovers) and aphorize that "Alcohol will kill anything that's alive and preserve anything that's dead."

So, my fellow Americans, what is the state of the Dylan? He's playing around 100-odd concerts a year, has switched from guitar to piano, is snarling "Like a Rolling Stone" from the casinos of Arizona to the ruins of Italy, and keeps close watch on his iconic image. He saw the dangers of his fame 40 years ago, back when he was badgering Hentoff, and ran as far as he could from the hippies parachuting onto his lawn and the freaks digging through his garbage. But we now live in an age of possibility. Dylan at 65 can let loose, spinning records, cracking bad jokes, and revealing his affection for the odd LL Cool J and Prince tune amid his dusty old Folkways reissues.

Could this finally be the kindler, gentler Dylan? And do the Dylan's best days still lie ahead? The man who was born 65 years ago today asked how many roads a man must walk down; he still keeps the questions coming. Now we must rise to the decisive moment, to make a Dylan and a world not gone wrong, but better than any we have known. We stand at the edge of a New Morning — the morning of unfulfilled hopes and 115 dreams, where the tour is never ending. Senators, congressmen, please heed the call. Thank you. God bless you, and God bless the Dylan. And may you stay forever young.

David Yaffe is assistant professor of English at Syracuse University and the author of Fascinating Rhythm: Reading Jazz in American Writing.

The State of the Dylan Address

An annual tradition.

By David Yaffe

Mr. Speaker, Vice President Cheney, members of Congress, readers of Slate, distinguished Fraysters, fellow citizens. Sixty-five years ago today, our Dylan was busy being born. He's older than that now. As he becomes a contender for the cover of AARP Magazine, it is my duty to report on the state of the Dylan.

It is true that money doesn't talk, it swears. Nevertheless, over the last six years, we have brought new economic growth by investing in our Dylan. According to the Office of Billboard and Budget, the Dylan's last CD of new material, Love and Theft, sold 754,000 copies, and the Dylan made $1 million in royalties from the book Chronicles Vol. 1. Now we move into a new age of technology: the Dylan's iTunes music store and XM Radio's Theme Time Radio Hour, hosted by the Dylan. Add to this the upcoming Twyla Tharp dance spectacle, a Todd Haynes biopic where seven different actors will play the Dylan, a new CD ready to hit stores, Michael Gray's comprehensive and up-to-date Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, and the perennial fact that he's still on the road, headin' for another joint, and it is unassailably clear: My fellow Americans, the state of the Dylan is strong. (Applause.)

Yet we are still, in the words of our founders, striving to form a more perfect Dylan. Anyone following the state of the Dylan will recognize the character in Jonathan Cott's Bob Dylan: The Essential Interviews, published this month. This is the Dylan who eviscerated a Time reporter and immortalized him as the clueless "Mr. Jones" of "Ballad of a Thin Man." The book charts four decades of exchanges: We get the yarn-spinning Dylan of the early '60s, the combative, elliptical drugged-out icon of the mid-'60s, the oracular converso of the late '70s, the embittered burnout of the '80s, the ailing comeback kid of the '90s, and the sexagenarian swami of the 21st century. The Dylan of XM Radio's Theme Time Radio Hour, however, is a Dylan both familiar and startling.

Listening to Dylan's show, we hear the chimes of freedom on the march. Back in 1966, Dylan was still battling uptight forces, even when confronted with the hep Nat Hentoff, who quoted him saying that people "hang out on the radio." Dylan corrected him: "I didn't say that people 'hang out' on the radio, I said they got 'hung up' on the radio." Forty years later, Dylan is definitely hanging out on the radio. There will be, as usual, the nattering nabobs of Dylanology ascribing monumental significance to every utterance he makes, but they would be missing the spirit of the show. Dylan is wisecracking, relaxed, and open on these satellite waves, rasping like Tom Waits' DJ character in Mystery Train. Each show has a theme; so far they've included "Weather," "Mother," "Drinking," and "Baseball." With each theme, Dylan has an excuse to spin records he likes, intone song lyrics like a gnomic bluesman, crack jokes, and reveal minor clues about his influences, such as when he kicks off his first show with Muddy Waters' "Blow, Wind, Blow," a "Blowin' in the Wind" source that bypassed most Dylanographers. On the "Baseball" episode, he even sings "Take Me Out to the Ball Game."

The Dylan, aided by an international coalition of researchers and probably reciting his patter from a tour bus or hotel room, tells a little anecdote about each artist he plays—the more obscure the better. But you can understand every word and, lo and behold, he actually seems to be enjoying himself. "Here's Sonny Rollins, covering all the bases," he rasps, introducing Rollins' "Newk's Getaway," breaking in just before Rollins' solo to interject, "Let's get goin'." By the time he gets to the third episode, "Drinking," he seems light-years away from the stonewalling Delphic oracle we know. The state of the Dylan might actually be getting mellower with age, but he is not in a malaise. Five years ago, when Mikal Gilmore asked him about his history with alcohol, Dylan snapped: "I can drink or not drink. I don't know why people would associate drinking or not drinking with anything that I do, really." But get the man behind the mic, and he'll offer his recipe for a mint julep (after Lenore from Cincinnati asked for it and he played "One Mint Julep" by the Clovers) and aphorize that "Alcohol will kill anything that's alive and preserve anything that's dead."

So, my fellow Americans, what is the state of the Dylan? He's playing around 100-odd concerts a year, has switched from guitar to piano, is snarling "Like a Rolling Stone" from the casinos of Arizona to the ruins of Italy, and keeps close watch on his iconic image. He saw the dangers of his fame 40 years ago, back when he was badgering Hentoff, and ran as far as he could from the hippies parachuting onto his lawn and the freaks digging through his garbage. But we now live in an age of possibility. Dylan at 65 can let loose, spinning records, cracking bad jokes, and revealing his affection for the odd LL Cool J and Prince tune amid his dusty old Folkways reissues.

Could this finally be the kindler, gentler Dylan? And do the Dylan's best days still lie ahead? The man who was born 65 years ago today asked how many roads a man must walk down; he still keeps the questions coming. Now we must rise to the decisive moment, to make a Dylan and a world not gone wrong, but better than any we have known. We stand at the edge of a New Morning — the morning of unfulfilled hopes and 115 dreams, where the tour is never ending. Senators, congressmen, please heed the call. Thank you. God bless you, and God bless the Dylan. And may you stay forever young.

David Yaffe is assistant professor of English at Syracuse University and the author of Fascinating Rhythm: Reading Jazz in American Writing.

Tuesday, May 23, 2006

Loveless, sampled

Here's a short passage from Mike McGonigal's book about Loveless, coming in September...

***

The most radical changes in pop music occur with shifts that might appear really minor from the outside but actually represent huge leaps. Often, it’s as simple as one tool being used for something it was never intended for, as with the turntable becoming a musical instrument via the scratch, or the 808 bass sampling keyboard getting tweaked to make crazy squelches. One of the things that flipped other musicians and producers out about Loveless is that the sampler is used as more than a phrase machine, largely because the band were sampling themselves. OK, maybe this isn’t such a "radical change in pop music," but the results do sound really cool.

"We chose non-organic sounds," says Shields; "that’s why people didn’t immediately go 'That’s a keyboard,' even though it is. There are multi-layered parts to some songs, like the opening of 'Only Shallow,' with me playing the same thing three or four times. It was the usual rock and roll bending the strings type of thing, but I had two amps facing each other, with two different tremolos on them. And I sampled it and put it an octave higher on the sampler. On Glider’s one guitar track, 'I Only Said,' that’s one guitar track and a couple of overdubs. A lot of the hooks were sampled vocals or feedback we didn’t want to use. You can hear it has the movement of natural sound. The 'synth' solo two thirds of the way through 'Sometimes' is Bilinda’s voice, and a little oboe sample in there from the keyboard itself."

"For us, where the sampler had a great value, was that instead of having the option to play things on a keyboard based on some sounds you could find anywhere, we’d sample our own guitar feedback, which instead of just being one tone, it could be a tone having bends and quirks in it," Shields explains. "And then, by using the human voice as well for the top end, you’ve got these organic things happening, even though sometimes you’re using keyboards to play them. You are letting the organic part be part of the rhythm of the sample. We’d edit them as such. God, so much of time we spent making the record was doing that kind of stuff. I mean, we did that massive experimentation thing in the summer of 1990, but before in 1989, one of the most sampled songs we created was ‘Glider.’ It’s just a guitar riff, and then something that sounds like gates creaking — and that’s all guitar feedback, loads and loads of guitar feedback that we just sampled and played in. But in those days we didn’t have a keyboard so we played it all by pressing the button on the sampler. So there wasn’t even a keyboard involved. It was just touching the sampler itself, you know?"

"Most of the songs have got samples on them," Kevin says. "On 'Soon,' there’s a bit that goes 'ah ah ah' where it sounds like Belinda’s voice — that’s just me hitting a key on the sampler — well it was actually a Bell delay unit, but we made a sample out of it. And the first thing in 'Only Shallow' — those kind of high sounds — that’s just a sample." At the time, they were fumbling in the dark to use these methods, but Shields notes that "everything we did is now just stock, normal, standard techniques for making music. We were just using the technology to achieve our aims." Everyone else using samplers at the time, like Pop Will Eat Itself or Age of Chance, "used their technology to make it sound like technology [stutters intentionally] — that 'N-N-N-N-Nineteen' type thing. What we did — and which then became the prominent way of using samplers — was to try and make it sound like you’re not using a sampler."

***

***

The most radical changes in pop music occur with shifts that might appear really minor from the outside but actually represent huge leaps. Often, it’s as simple as one tool being used for something it was never intended for, as with the turntable becoming a musical instrument via the scratch, or the 808 bass sampling keyboard getting tweaked to make crazy squelches. One of the things that flipped other musicians and producers out about Loveless is that the sampler is used as more than a phrase machine, largely because the band were sampling themselves. OK, maybe this isn’t such a "radical change in pop music," but the results do sound really cool.

"We chose non-organic sounds," says Shields; "that’s why people didn’t immediately go 'That’s a keyboard,' even though it is. There are multi-layered parts to some songs, like the opening of 'Only Shallow,' with me playing the same thing three or four times. It was the usual rock and roll bending the strings type of thing, but I had two amps facing each other, with two different tremolos on them. And I sampled it and put it an octave higher on the sampler. On Glider’s one guitar track, 'I Only Said,' that’s one guitar track and a couple of overdubs. A lot of the hooks were sampled vocals or feedback we didn’t want to use. You can hear it has the movement of natural sound. The 'synth' solo two thirds of the way through 'Sometimes' is Bilinda’s voice, and a little oboe sample in there from the keyboard itself."

"For us, where the sampler had a great value, was that instead of having the option to play things on a keyboard based on some sounds you could find anywhere, we’d sample our own guitar feedback, which instead of just being one tone, it could be a tone having bends and quirks in it," Shields explains. "And then, by using the human voice as well for the top end, you’ve got these organic things happening, even though sometimes you’re using keyboards to play them. You are letting the organic part be part of the rhythm of the sample. We’d edit them as such. God, so much of time we spent making the record was doing that kind of stuff. I mean, we did that massive experimentation thing in the summer of 1990, but before in 1989, one of the most sampled songs we created was ‘Glider.’ It’s just a guitar riff, and then something that sounds like gates creaking — and that’s all guitar feedback, loads and loads of guitar feedback that we just sampled and played in. But in those days we didn’t have a keyboard so we played it all by pressing the button on the sampler. So there wasn’t even a keyboard involved. It was just touching the sampler itself, you know?"

"Most of the songs have got samples on them," Kevin says. "On 'Soon,' there’s a bit that goes 'ah ah ah' where it sounds like Belinda’s voice — that’s just me hitting a key on the sampler — well it was actually a Bell delay unit, but we made a sample out of it. And the first thing in 'Only Shallow' — those kind of high sounds — that’s just a sample." At the time, they were fumbling in the dark to use these methods, but Shields notes that "everything we did is now just stock, normal, standard techniques for making music. We were just using the technology to achieve our aims." Everyone else using samplers at the time, like Pop Will Eat Itself or Age of Chance, "used their technology to make it sound like technology [stutters intentionally] — that 'N-N-N-N-Nineteen' type thing. What we did — and which then became the prominent way of using samplers — was to try and make it sound like you’re not using a sampler."

***

Monday, May 22, 2006

Book Expo, Sly Stone, Dylan

Got back from Book Expo in DC yesterday. Considering it was the first time Continuum had taken a booth there for a few years (hence, they quite reasonably gave us a crappy spot in the massive exhibit hall), it went very well. Met lots of people, handed out lots of freebies, got lavished with food and alcohol by our dear friends at Google. Next year, BEA returns to the Javits Centre in NYC - we'll have a better location, much more free stuff, and we'll put together a kick-ass 33 1/3 party, too.

*****

Two reviews of Miles Marshall Lewis' Sly Stone book:

The Source (May 2006), by Sidik Fofana -- "Miles Marshall Lewis analyzes one of the essential funk albums, Sly and the Family Stone's There's a Riot Goin' On. Complete with behind-the-scenes accounts, the book goes inside Sly's troubled psyche."

Under the Radar (Spring 2006), by Cory Frye -- "Everybody loves writing about Sly Stone. Griel Marcus did it best in Mystery Train, and Miles Marshall Lewis gives it a shot here, focusing on There's a Riot Goin' On, Sly and the Family's Stone's blue-ribbon masterpiece, and angry (and classic) avowal of the hippie virtues they'd previously cross-haired at the toppermost charts.

Lewis's study is straightforward, academic, and thoroughly researched. It's marred ever so slightly by a self-conscious tendency to occasionally dust a phrase with slang, as if to assure the reader Miles is smart and down; there's also a prelude of unnecessary fictional dialogue between father and son. But the rest is all biscuits for those of us who loved the man his mama called Sylvester. 8 blips out of 10

*****

And there's an oddly dispiriting piece in the New York Times today by Janet Maslin - a joint review of our upcoming Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, and Jonathan Cott's recently released Bob Dylan: The Essential Interviews. Maslin devotes far more time to Cott's book than to Gray's and concludes by saying, in effect, that we should let Bob speak for himself and trust in his version of the truth, as found in Chronicles. Hmmmm - not sure about that. Maslin also refers to Gray's entry on Jonathan Cott as "snarky", which I truly don't believe it is. Judge for yourself:

Cott, Jonathan [1942 - ]

Jonathan Cott was born in New York City on December 24, 1942, and lives there still. His books include Wandering Ghost: The Odyssey of Lafcadio Hearn, Conversations with Glenn Gould and, in fall 2005, the extraordinary On the Sea of Memory: A Journey from Forgetting to Remembering, prompted by what happened to Cott at the end of the 1990s, when, after electroshock treatments for severe clinical depression, he could remember nothing he had experienced between 1985 and 2000. The book combines autobiography with a scrutiny of ‘the mysteries of human memory’ and the roles played in our lives by both remembering and forgetting.

Cott first took an interest in Dylan when he saw him perform in a Greenwich Village cafe in 1963 and bought The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. His first published work about him was an article/review of Eat the Document in Rolling Stone in 1971. He has also written one book about him and edited another. The first, Dylan, mixing criticism with biography and collecting terrific photographs, is from 1985; the second, Dylan: The Essential Interviews, is from 2006.

In 1978 Cott interviews Dylan himself—on a bus from Portland, Maine, to the airport, on the plane to New Haven, CT, and in his dressing room at the Veterans’ Memorial Coliseum, on September 17, 1978. When he asks about the 1978 album Street Legal, a classic encounter between the interpreter and the artist ensues, as TERRY KELLY points up (albeit with a bad case of mixed metaphors): ‘Cott fires an arsenal of quotations and references he finds relevant to ‘‘Changing of the Guards’’ at a typically taciturn Dylan. The loquacious Cott builds up to a tidal wave of feverish explication, peppered with Tarot card references, songwriting sub-codes and . . . subconscious images. . . . He tells a still-silent Dylan that he believes each floor of ‘‘the palace of mirrors’’ contains another significant image or level of awareness. . . . After what seems like a lifetime of silence, Dylan eventually puts Cott out of his misery. ‘‘I think,’’ Dylan mumbles, ‘‘you might be in some areas I’m not too familiar with.’’’

*****

Two reviews of Miles Marshall Lewis' Sly Stone book:

The Source (May 2006), by Sidik Fofana -- "Miles Marshall Lewis analyzes one of the essential funk albums, Sly and the Family Stone's There's a Riot Goin' On. Complete with behind-the-scenes accounts, the book goes inside Sly's troubled psyche."

Under the Radar (Spring 2006), by Cory Frye -- "Everybody loves writing about Sly Stone. Griel Marcus did it best in Mystery Train, and Miles Marshall Lewis gives it a shot here, focusing on There's a Riot Goin' On, Sly and the Family's Stone's blue-ribbon masterpiece, and angry (and classic) avowal of the hippie virtues they'd previously cross-haired at the toppermost charts.

Lewis's study is straightforward, academic, and thoroughly researched. It's marred ever so slightly by a self-conscious tendency to occasionally dust a phrase with slang, as if to assure the reader Miles is smart and down; there's also a prelude of unnecessary fictional dialogue between father and son. But the rest is all biscuits for those of us who loved the man his mama called Sylvester. 8 blips out of 10

*****

And there's an oddly dispiriting piece in the New York Times today by Janet Maslin - a joint review of our upcoming Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, and Jonathan Cott's recently released Bob Dylan: The Essential Interviews. Maslin devotes far more time to Cott's book than to Gray's and concludes by saying, in effect, that we should let Bob speak for himself and trust in his version of the truth, as found in Chronicles. Hmmmm - not sure about that. Maslin also refers to Gray's entry on Jonathan Cott as "snarky", which I truly don't believe it is. Judge for yourself:

Cott, Jonathan [1942 - ]

Jonathan Cott was born in New York City on December 24, 1942, and lives there still. His books include Wandering Ghost: The Odyssey of Lafcadio Hearn, Conversations with Glenn Gould and, in fall 2005, the extraordinary On the Sea of Memory: A Journey from Forgetting to Remembering, prompted by what happened to Cott at the end of the 1990s, when, after electroshock treatments for severe clinical depression, he could remember nothing he had experienced between 1985 and 2000. The book combines autobiography with a scrutiny of ‘the mysteries of human memory’ and the roles played in our lives by both remembering and forgetting.

Cott first took an interest in Dylan when he saw him perform in a Greenwich Village cafe in 1963 and bought The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. His first published work about him was an article/review of Eat the Document in Rolling Stone in 1971. He has also written one book about him and edited another. The first, Dylan, mixing criticism with biography and collecting terrific photographs, is from 1985; the second, Dylan: The Essential Interviews, is from 2006.

In 1978 Cott interviews Dylan himself—on a bus from Portland, Maine, to the airport, on the plane to New Haven, CT, and in his dressing room at the Veterans’ Memorial Coliseum, on September 17, 1978. When he asks about the 1978 album Street Legal, a classic encounter between the interpreter and the artist ensues, as TERRY KELLY points up (albeit with a bad case of mixed metaphors): ‘Cott fires an arsenal of quotations and references he finds relevant to ‘‘Changing of the Guards’’ at a typically taciturn Dylan. The loquacious Cott builds up to a tidal wave of feverish explication, peppered with Tarot card references, songwriting sub-codes and . . . subconscious images. . . . He tells a still-silent Dylan that he believes each floor of ‘‘the palace of mirrors’’ contains another significant image or level of awareness. . . . After what seems like a lifetime of silence, Dylan eventually puts Cott out of his misery. ‘‘I think,’’ Dylan mumbles, ‘‘you might be in some areas I’m not too familiar with.’’’

Wednesday, May 17, 2006

Beastie Boys review

Here's a review by Jake Haselman from www.indieworkshop.com, of Dan LeRoy's book about Paul's Boutique:

***

Who would have thought that the creation of one of Hip-Hop's masterpieces would be a drug fueled, party soaked, apartment recorded album that took the better part of a year to finish? Well, it was. And who would have thought that three white kids from Brooklyn would be the ones to drop it? But they were. While the Beasties were flying high off the success of their debut album, License to Ill, they were still on the outside looking in to the core of the Hip Hop elite. And while it's not really tackled a whole lot in this book, I don't really think the Beastie Boys had a whole lot of fans inside the Hip Hop world. I don't think anyone took that first album seriously, I mean, it was an anthem to the MTV crowd.

But everything changed.

After the world tour for License to Ill ended, the Beasties were in shambles. Their fight with Russell Simmons and Def Jam were just about to start, the relationships within the band were strained… they were emotionally and physically exhausted. So looking for some R and R, and a fresh start, the B Boy's packed up and headed out west to LA. While reenergizing and blowing off steam, the guys meet up with Matt Dike and the Dust Brothers (before they were even the Dust Brothers) and before you know it, all night meetings were taking place in Dike's apartment.

The story of the actual construction of the album is amazing. With what would now be considered primitive means, these mad scientists were creating fantastically complex beats. Looping drum beats and guitar lines from all over the music world all with little more than a record player, a reel to reel, and their hands. It's really quiet astounding to think that they didn't even have a mixing board with automation, this really was done by hand.

Dan LeRoy paints a picture of three young men discovering their talent. He also sheds light on the lesser-known players in this momentous album. People like Matt Dike hardly get the praise when people start talking about the Beasties. But after reading this book, and knowing how the Beasties turned out (sound wise), I'd say that Dike and the Dust Brothers had more influence on these three than Rick Rubin.

Their excessive partying and delay after delay with the album stretched their relationship with Capitol to its breaking point. Once the album failed to do well upon release, the Boy's were left to practically start over from square one. They couldn't tour, places they had demolished on the first tour wouldn't have them back. And the sluggish sales forced them to slink back into the club circuit. The world wasn't ready for Paul's Boutique.

But older and wiser, the rest of the world has come around to see what the critics were talking about. The Beastie Boys had shed their party boy, frat-house fan base. It wasn't easy, and it wasn't a painless process, but the initial failure of this album in the public was probably the best thing to happen to these guys. Real Hip Hop fans started to pay attention to them, and not just for their antics. Slowly but surly, people started to realize the powerful record that was created. People started to respect what these cats were up to. People started to become real fans. This is when everything changed, not just for The Beastie Boys, but for music as a whole.

LeRoy has crafted a short, fun read out of a highly overlooked period in this band's life. From the late night brainstorming sessions to the egg tossing to the finished product, it's all in here. This is a great book about an amazing record.

***

Who would have thought that the creation of one of Hip-Hop's masterpieces would be a drug fueled, party soaked, apartment recorded album that took the better part of a year to finish? Well, it was. And who would have thought that three white kids from Brooklyn would be the ones to drop it? But they were. While the Beasties were flying high off the success of their debut album, License to Ill, they were still on the outside looking in to the core of the Hip Hop elite. And while it's not really tackled a whole lot in this book, I don't really think the Beastie Boys had a whole lot of fans inside the Hip Hop world. I don't think anyone took that first album seriously, I mean, it was an anthem to the MTV crowd.

But everything changed.

After the world tour for License to Ill ended, the Beasties were in shambles. Their fight with Russell Simmons and Def Jam were just about to start, the relationships within the band were strained… they were emotionally and physically exhausted. So looking for some R and R, and a fresh start, the B Boy's packed up and headed out west to LA. While reenergizing and blowing off steam, the guys meet up with Matt Dike and the Dust Brothers (before they were even the Dust Brothers) and before you know it, all night meetings were taking place in Dike's apartment.

The story of the actual construction of the album is amazing. With what would now be considered primitive means, these mad scientists were creating fantastically complex beats. Looping drum beats and guitar lines from all over the music world all with little more than a record player, a reel to reel, and their hands. It's really quiet astounding to think that they didn't even have a mixing board with automation, this really was done by hand.

Dan LeRoy paints a picture of three young men discovering their talent. He also sheds light on the lesser-known players in this momentous album. People like Matt Dike hardly get the praise when people start talking about the Beasties. But after reading this book, and knowing how the Beasties turned out (sound wise), I'd say that Dike and the Dust Brothers had more influence on these three than Rick Rubin.

Their excessive partying and delay after delay with the album stretched their relationship with Capitol to its breaking point. Once the album failed to do well upon release, the Boy's were left to practically start over from square one. They couldn't tour, places they had demolished on the first tour wouldn't have them back. And the sluggish sales forced them to slink back into the club circuit. The world wasn't ready for Paul's Boutique.

But older and wiser, the rest of the world has come around to see what the critics were talking about. The Beastie Boys had shed their party boy, frat-house fan base. It wasn't easy, and it wasn't a painless process, but the initial failure of this album in the public was probably the best thing to happen to these guys. Real Hip Hop fans started to pay attention to them, and not just for their antics. Slowly but surly, people started to realize the powerful record that was created. People started to respect what these cats were up to. People started to become real fans. This is when everything changed, not just for The Beastie Boys, but for music as a whole.

LeRoy has crafted a short, fun read out of a highly overlooked period in this band's life. From the late night brainstorming sessions to the egg tossing to the finished product, it's all in here. This is a great book about an amazing record.

Book Expo America

The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia

We're getting thrillingly close to the publication of Michael Gray's new Dylan book, which is being printed simulataneously in the US and the UK and will be available everywhere by June 15th.

This week's entry (scroll down for previous entries, on Dave Stewart, Leonard Cohen, Fats Domino and Harry Belafonte) is a little different:

***

blues, inequality of reward in

The inequality of reward and credit as between the old black singer-songwriters and the newer white ones is a topic that arises unavoidably from any scrutiny of what Dylan has taken from the blues.

Four years after the beginning of Dylan’s recording career, and already a superstar, he is visiting Tennessee, the state in which Memphis is located, to record the deeply blues-soaked album Blonde on Blonde. In Memphis itself, ELVIS PRESLEY is residing in decadent luxury, resting on the laurels of a career launched from the Sun studios on a cover version of an ARTHUR CRUDUP blues at a time when Arthur Crudup wouldn’t even have been allowed to ride alongside Presley on a public bus. (Not that Crudup was in Memphis; he’d migrated to Chicago, where to begin with he’d lived in a wooden crate under the ‘L’ station.)

While Dylan is recording ‘Pledging My Time’, and Elvis is playing games at Graceland, 40 miles south of Memphis on Highway 51, Mississippi Fred McDowell, that state’s greatest living bluesman and a big influence on Ry Cooder and Bonnie Raitt, is working in a gas-station in Como, Mississippi. As Stanley Booth notes in his appealing book Rythm Oil, ‘there is a telephone handy for when he gets calls to appear at places like the NEWPORT FOLK FESTIVAL.’

What can you say? Several things. Elvis had to live his whole adult life with the accusation that he’d somehow stolen this music, and had only succeeded at it because he was white. This is in every detail untrue. First, Elvis’ early record producer, Sam Phillips, recorded Elvis singing blues because they both loved it; Phillips launched the careers of black artists (HOWLIN’ WOLF included) as well as white, and willingly let each move on to bigger things than Sun could accommodate.

Against the wishes of his manager Colonel Parker, Elvis continued to record black material throughout his life, because his love for it remained undimmed when precious little else did. Rightly he credited its composers on his records and paid them songwriting royalties. That his own music-publishing outfits took hefty proportions was a corrupt practice endemic in the industry then and now, and applied equally to the white songwriters who hit the theoretical jackpot of having Presley record their material. Low royalty rates, and royalties flowing into the wrong pockets, were aspects of the business that applied without regard to race. ROY ORBISON recalled that he’d been signed to Sun Records for quite a while before he heard, from an older songwriter, that you were supposed to get paid when they played your songs on the radio—and when Orbison told CARL PERKINS, it was news to him too.

It’s a myth too that Elvis stole ‘Hound Dog’ from Big Mama Thornton. White Jewish songwriters Leiber & Stoller wrote it, and offered it to Johnny Otis; he offered it to Thornton and stole the composer credit, which, as GREIL MARCUS wrote in his classic book Mystery Train, ‘Leiber and Stoller had to fight to get back. Elvis heard the record, changed the song completely, from the tempo to the words, and cut Thornton’s version to shreds.’

Elvis made this material his own; he did something special with all of it. He couldn’t have ignited a revolution through unfair good luck. That’s the essence of it. And Dylan too takes from the blues because he loves it, and then makes of it something his own. It’s a creative process, and creativity deserves success.

That success doesn’t always come, that life is essentially unfair, is also true, but beyond the capacity of a Presley or a Dylan to affect. Neither is its unfairness racially scrupulous. Consider the case of another old blues singer, FURRY LEWIS, about whom no black writer or singer has ever said a word but of whom white Stanley Booth writes at length. Like Hubert Sumlin, Furry Lewis came from Greenwood, Mississippi, but he moved to Memphis at the age of six, in 1899. At 23, he lost a leg trying to catch a freight train outside Du Quoin, Illinois. A protege of W.C. Handy, he recorded four sessions in the 1920s but the depression killed off his career and he didn’t record again till 1959. After the end of the 1920s he was never again a full-time pro. He isn’t mentioned in Louis Cantor’s history of Memphis-based WDIA, the first all-black radio station: 230 pages on how this wonderful station gave blacks their own voice and put the blues on the air—but no change for a bluesman of Lewis’ generation: he was still excluded. So was FRANK STOKES, another giant of the early Memphis blues scene who was still alive and living in neglect in Memphis when Elvis made his first records there. Stokes died, aged 67, in 1955. ‘Frank Stokes: Creator of the Memphis Blues’, the reissue label Yazoo was calling him two decades later.

Then there are the salutary cases of the innovative Noah Lewis and of GUS CANNON, another towering Memphis figure. When Bob Dylan chose to open his performance at the 1996 Aarhus Festival, Denmark, with an approximation of THE GRATEFUL DEAD’s ‘New New Minglewood Blues’, he’s likely to have chosen it not because it’s a Dead song but because it isn’t: because, rather, it’s based on ‘New Minglewood Blues’ by Noah Lewis’s Jug Band from 1930, itself a re-modelling of ‘Minglewood Blues’ by Cannon’s Jug Stompers (comprising, in this instance, Gus Cannon, Ashley Thompson and Noah Lewis) from 1928. The Dead’s recording may well have reminded Dylan of the song, but there’s no reason to suppose that he hadn’t been familiar with the original Noah Lewis’s Jug Band recording, since this had been vinyl-reissued in the early 1960s. The key figure here, then, is the pioneering and splendid harmonica-player Noah Lewis, whose work set new expressive standards in the pre-war period (and who is credited as the composer of ‘Minglewood Blues’ as well as of ‘New Minglewood Blues’: the two may share a tune but are otherwise dissimilar songs—different in lyrics, pace and mood). Lewis was long thought to have been murdered in 1937, but Swedish researcher Bent Olsson discovered that in fact he had retired to Ripley, Tennessee, in the 30s, where in his old age he got frostbite, had both legs amputated and in the process got blood-poisoning, from which he died in the winter of early 1961.

Cannon was by far the better-known figure by the time Bob Dylan reached Greenwich Village. He was one of the featured artists on both HARRY SMITH’s 1952 anthology AMERICAN FOLK MUSIC and on the next crucial release of the period, SAM CHARTERS’ 1959 compilation Country Blues. Cannon’s track on the former, indeed, was ‘Minglewood Blues’ while on the latter was his 1929 cut ‘Walk Right In’, which was taken up by the Rooftop Singers, who topped the US charts with a single of the song, complete with beefy 12-string guitar sound, in 1963.

Cannon’s own career was first ‘revived’ in 1956 when he was recorded, for the first time since 1930, by Folkways. They let him cut two tracks. Then in 1963, in the wake of the Rooftop Singers’ success, Cannon cut an album issued by Stax (!) which featured ‘Walk Right In’ plus standards like ‘Salty Dog’, ‘Boll-Weevil’ and ‘Make Me a Pallet on Your Floor’. He also made appearances at the Newport Folk Festival. He survived to the age of 96, living long enough to still be around in Memphis at the time of Elvis Presley’s funeral there in 1977.

Despite his eminence and his ‘rediscovery’, Gus Cannon too suffered neglect, poverty and lack of respect. His situation is described eloquently by Jim Dickinson, the Memphis session-player who features on Dylan’s Time Out of Mind album twenty years after Cannon’s death:

‘In the summer of 1960, a friend and I followed the trail that Charters left to Gus Cannon. . . . He was the yardman for an anthropology professor. Gus had told this family that he used to make records and he had been on RCA and they’d say, ‘‘Yeah Gus, sure: cut the grass.’’ . . . He lived on the property, back over a garage, and he took us up into his room, and on the wall he had a certificate for sales from ‘Walk Right In’, for which of course he didn’t get any money. And he had a copy of the record that Charters had made for Folkways, but he had no record-player. That was a real good introduction to the blues.’

Likewise, right through to the 1970s Furry Lewis remained a street-sweeper in Memphis. Now and then in the mid-1960s he’d play a set between rock acts at the Bitter Lemon coffee-house in East Memphis. Stanley Booth writes: ‘Next morning he’s back sweeping the streets. At the crack of dawn, on his way to work, he passes the Club Handy. On the door is a handbill that reads Blues Spectacular, City Auditorium: JIMMY REED, JOHN LEE HOOKER, Howlin’ Wolf . . .’

Inequality of reward, like the blues itself, works on many levels.

***

This week's entry (scroll down for previous entries, on Dave Stewart, Leonard Cohen, Fats Domino and Harry Belafonte) is a little different:

***

blues, inequality of reward in

The inequality of reward and credit as between the old black singer-songwriters and the newer white ones is a topic that arises unavoidably from any scrutiny of what Dylan has taken from the blues.

Four years after the beginning of Dylan’s recording career, and already a superstar, he is visiting Tennessee, the state in which Memphis is located, to record the deeply blues-soaked album Blonde on Blonde. In Memphis itself, ELVIS PRESLEY is residing in decadent luxury, resting on the laurels of a career launched from the Sun studios on a cover version of an ARTHUR CRUDUP blues at a time when Arthur Crudup wouldn’t even have been allowed to ride alongside Presley on a public bus. (Not that Crudup was in Memphis; he’d migrated to Chicago, where to begin with he’d lived in a wooden crate under the ‘L’ station.)

While Dylan is recording ‘Pledging My Time’, and Elvis is playing games at Graceland, 40 miles south of Memphis on Highway 51, Mississippi Fred McDowell, that state’s greatest living bluesman and a big influence on Ry Cooder and Bonnie Raitt, is working in a gas-station in Como, Mississippi. As Stanley Booth notes in his appealing book Rythm Oil, ‘there is a telephone handy for when he gets calls to appear at places like the NEWPORT FOLK FESTIVAL.’

What can you say? Several things. Elvis had to live his whole adult life with the accusation that he’d somehow stolen this music, and had only succeeded at it because he was white. This is in every detail untrue. First, Elvis’ early record producer, Sam Phillips, recorded Elvis singing blues because they both loved it; Phillips launched the careers of black artists (HOWLIN’ WOLF included) as well as white, and willingly let each move on to bigger things than Sun could accommodate.

Against the wishes of his manager Colonel Parker, Elvis continued to record black material throughout his life, because his love for it remained undimmed when precious little else did. Rightly he credited its composers on his records and paid them songwriting royalties. That his own music-publishing outfits took hefty proportions was a corrupt practice endemic in the industry then and now, and applied equally to the white songwriters who hit the theoretical jackpot of having Presley record their material. Low royalty rates, and royalties flowing into the wrong pockets, were aspects of the business that applied without regard to race. ROY ORBISON recalled that he’d been signed to Sun Records for quite a while before he heard, from an older songwriter, that you were supposed to get paid when they played your songs on the radio—and when Orbison told CARL PERKINS, it was news to him too.

It’s a myth too that Elvis stole ‘Hound Dog’ from Big Mama Thornton. White Jewish songwriters Leiber & Stoller wrote it, and offered it to Johnny Otis; he offered it to Thornton and stole the composer credit, which, as GREIL MARCUS wrote in his classic book Mystery Train, ‘Leiber and Stoller had to fight to get back. Elvis heard the record, changed the song completely, from the tempo to the words, and cut Thornton’s version to shreds.’

Elvis made this material his own; he did something special with all of it. He couldn’t have ignited a revolution through unfair good luck. That’s the essence of it. And Dylan too takes from the blues because he loves it, and then makes of it something his own. It’s a creative process, and creativity deserves success.

That success doesn’t always come, that life is essentially unfair, is also true, but beyond the capacity of a Presley or a Dylan to affect. Neither is its unfairness racially scrupulous. Consider the case of another old blues singer, FURRY LEWIS, about whom no black writer or singer has ever said a word but of whom white Stanley Booth writes at length. Like Hubert Sumlin, Furry Lewis came from Greenwood, Mississippi, but he moved to Memphis at the age of six, in 1899. At 23, he lost a leg trying to catch a freight train outside Du Quoin, Illinois. A protege of W.C. Handy, he recorded four sessions in the 1920s but the depression killed off his career and he didn’t record again till 1959. After the end of the 1920s he was never again a full-time pro. He isn’t mentioned in Louis Cantor’s history of Memphis-based WDIA, the first all-black radio station: 230 pages on how this wonderful station gave blacks their own voice and put the blues on the air—but no change for a bluesman of Lewis’ generation: he was still excluded. So was FRANK STOKES, another giant of the early Memphis blues scene who was still alive and living in neglect in Memphis when Elvis made his first records there. Stokes died, aged 67, in 1955. ‘Frank Stokes: Creator of the Memphis Blues’, the reissue label Yazoo was calling him two decades later.

Then there are the salutary cases of the innovative Noah Lewis and of GUS CANNON, another towering Memphis figure. When Bob Dylan chose to open his performance at the 1996 Aarhus Festival, Denmark, with an approximation of THE GRATEFUL DEAD’s ‘New New Minglewood Blues’, he’s likely to have chosen it not because it’s a Dead song but because it isn’t: because, rather, it’s based on ‘New Minglewood Blues’ by Noah Lewis’s Jug Band from 1930, itself a re-modelling of ‘Minglewood Blues’ by Cannon’s Jug Stompers (comprising, in this instance, Gus Cannon, Ashley Thompson and Noah Lewis) from 1928. The Dead’s recording may well have reminded Dylan of the song, but there’s no reason to suppose that he hadn’t been familiar with the original Noah Lewis’s Jug Band recording, since this had been vinyl-reissued in the early 1960s. The key figure here, then, is the pioneering and splendid harmonica-player Noah Lewis, whose work set new expressive standards in the pre-war period (and who is credited as the composer of ‘Minglewood Blues’ as well as of ‘New Minglewood Blues’: the two may share a tune but are otherwise dissimilar songs—different in lyrics, pace and mood). Lewis was long thought to have been murdered in 1937, but Swedish researcher Bent Olsson discovered that in fact he had retired to Ripley, Tennessee, in the 30s, where in his old age he got frostbite, had both legs amputated and in the process got blood-poisoning, from which he died in the winter of early 1961.

Cannon was by far the better-known figure by the time Bob Dylan reached Greenwich Village. He was one of the featured artists on both HARRY SMITH’s 1952 anthology AMERICAN FOLK MUSIC and on the next crucial release of the period, SAM CHARTERS’ 1959 compilation Country Blues. Cannon’s track on the former, indeed, was ‘Minglewood Blues’ while on the latter was his 1929 cut ‘Walk Right In’, which was taken up by the Rooftop Singers, who topped the US charts with a single of the song, complete with beefy 12-string guitar sound, in 1963.

Cannon’s own career was first ‘revived’ in 1956 when he was recorded, for the first time since 1930, by Folkways. They let him cut two tracks. Then in 1963, in the wake of the Rooftop Singers’ success, Cannon cut an album issued by Stax (!) which featured ‘Walk Right In’ plus standards like ‘Salty Dog’, ‘Boll-Weevil’ and ‘Make Me a Pallet on Your Floor’. He also made appearances at the Newport Folk Festival. He survived to the age of 96, living long enough to still be around in Memphis at the time of Elvis Presley’s funeral there in 1977.